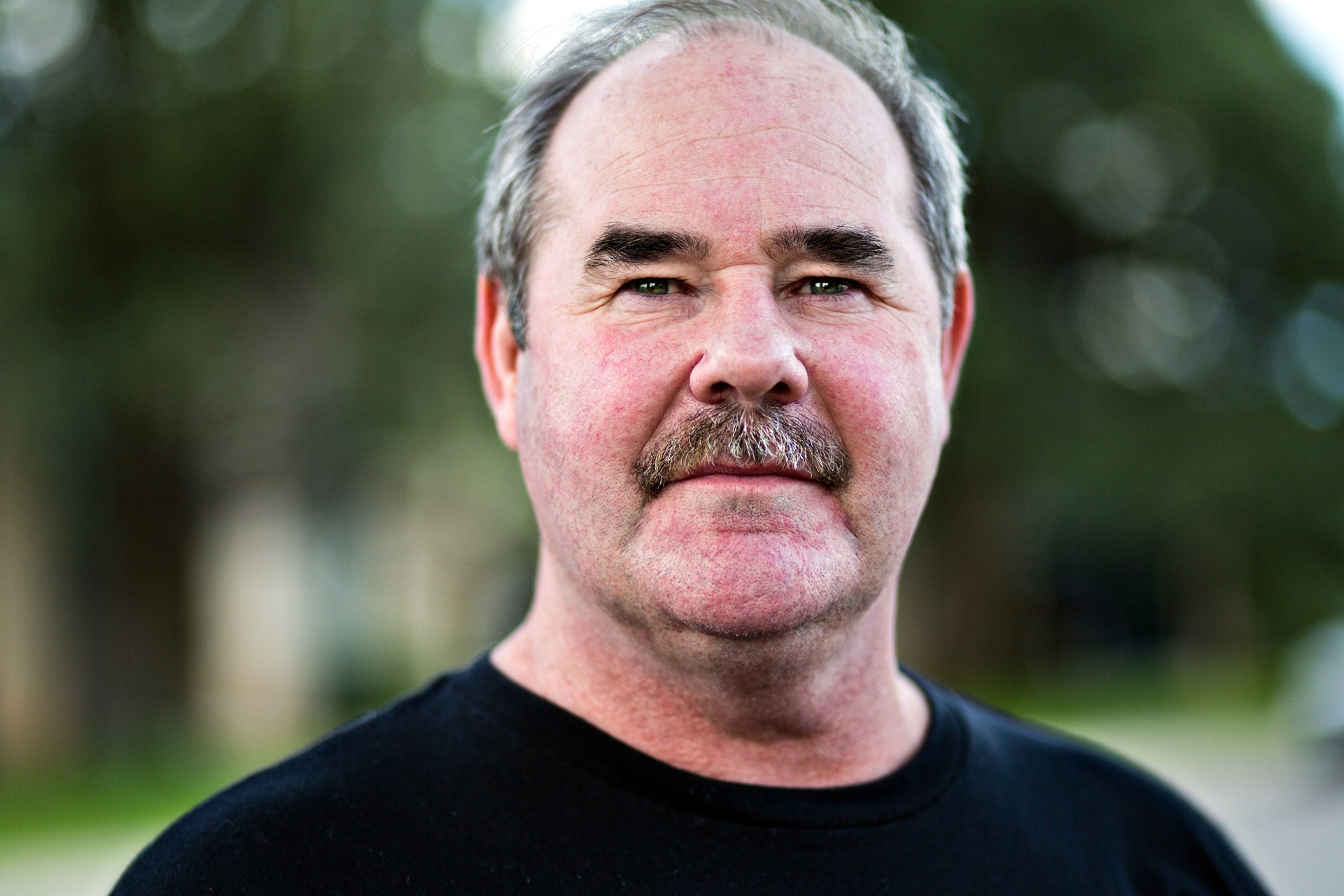

Guy Maxwell

is a suicide attempt survivor."I survived a suicide attempt."

Guy Maxwell is the program director for a methadone clinic in Albuquerque. He was born in Minnesota and raised in Kansas. He was 57 years old when I interviewed him in Albuquerque, NM on October 1, 2016.

CONTENT WARNING: graphic description of domestic violence and suicide attempt

My father was very unhappy. He drank a lot and he suffered from diabetes. He couldn’t regulate it. He was taking two shots a day, and that was back in the 70s. As far back as I can remember, he had a tackle box full of medications because he was a vet from the army.

Back then, you really didn’t have to go in and see the doctor but maybe once or twice a year. What happened was, he would go in and see a doctor. Well, that doctor had moved on, and there was another doctor to replace him. But the medications he was getting from the first doctor kept coming through the mail, and he got more medications from the second doctor or third, and so on. That’s how he ended up with a tackle box with everything from aspirin to barbiturates. My dad was a drug addict without even knowing it. He was following the doctor’s orders.

Anyway, very unhappy person. My mom was ruled by him. We were not a happy family. We didn’t tell each other, “Love ya, Mom. Love ya, Dad.” No hugs. When my dad did know that he was wrong, he didn’t just come out and say, “Hey son, I want to apologize.” He would try to crack some joke and then it would just be on, and I knew what he was trying to do was apologize. We never had a really close relationship.

Now I’m going to skip around here a little bit, but the closest I ever felt to my dad, I was in high school. We lived on this ten-acre farm outside of Atchison, Kansas. I was already into sniffing glue and sniffing gasoline. I didn’t intend to start doing that by saying, “I’m going to get messed up.” I was building a lot of models back then because I could do that by myself, and one day I thought the glue smelled good. I started smelling it, and then I got this buzz going. Same thing with gasoline. I was filling up the tractor one day, and the gasoline smelled good so I just started sniffing it.

One day I was down in the barn, and there was a five-gallon container of paint thinner. I sat on the floor and put the five-gallon jug in between my legs, I uncapped it, and I started huffing it. I passed out. By that time, I think Mom and Dad had come home from work, and my dad was looking for me. He came down to the barn and discovered me passed out over this five-gallon jug of paint thinner.

He picked me up. When I came to, we were walking in the grass. He was holding me up. I looked up at him and saw the fear and concern in his eyes. That was the closest I ever felt to my dad, that moment. That’s twisted, but you probably hear a lot of things like that.

Grade school was just grade school. I wasn’t allowed to do a whole lot. We were latchkey kids. Mom and Dad worked at Fort Leavenworth, and we had chores to do when we got home from the school. In the summertime, it was check the crops, and do the hoeing in between the beets, green peppers, and carrots. All that. I loved that. We also had one acre of tomato plants—three hundred plants. When they started coming in, that was my biggest job: go down and pick two or three bushels of tomatoes all at once and bring them up to the house for Mom to can.

Dad used the word “fuck” a lot. I thought my name was “motherfucker” or “Jesus Christ” until I was old enough to know better. He tried to teach me his work ethics, but he really sucked at being a good teacher. He taught me how to weld—and weld well—before I could even drive a tractor, but he beat it into me. He would have his helmet, I would have my helmet, and I would strike the arc. If I broke the arc, he would reach over and slap my helmet.

One day, I was mowing the grass on a riding lawnmower. I couldn’t figure out what was going on. I looked up to the house and Dad had come out on the porch. He’s 6’3” and was very, very skinny. He always wore bib overalls and had a Tareyton cigarette in his hands at all times. He’d come running down towards me, and I thought, “This can’t be good.” I couldn’t even hear what he was saying, but he hauled off and hit me with his fist as hard as he could. Knocked me off the mower and told me he wanted me to mow the grass in the other direction.

In a nutshell, that’s what my home life was like.

My first time I got away from Dad, I was a junior in high school getting ready to be a senior. During the summer, I had a chance to take off on a wheat harvest and go way away from my dad. We spent eighty-one days, from Oklahoma up to Wyoming, cutting wheat in different states. I lost about thirty-five pounds having fun and working hard. It was a lot of work. That’s when I knew I had to get away from my dad. I prayed many nights that he would die. I knew that was wrong, but there were times when I thought, “Just take him. What’s the deal?”

I had a friend next door, across the country road, about two hundred yards away, named Chip. Chip and I would hang out quite a bit. [His family] was Baptist. They went [to church] Wednesday night and twice on Sunday. I did, too. I was on the debate team. We had to memorize Bible verses and then go to different towns.

I actually loved being with that family. They hugged each other, said that they were sorry, and said they loved each other. We prayed and all that kind of stuff, and I thought that was awesome. I was spending a lot of time with their family.

Well, my dad came home one day. We lived in a double-wide trailer and he caught me in the hallway. He says, “Boy, I need you around here.” We only had ten acres, and we had a Ford 8N tractor. That was it. He said, “I need you around here. I need you to quit running around doing whatever. You like them so much? Why don’t you just go pack your shit and move over there? Just do it. Just do it.”

There went my balloon. The bubble got popped. I quit going to church so much with them and then got back into sniffing the glue. I got to the point where I was even in the closet because, double-wide mobile homes, back then, the walls were still only about a half an inch thick. If I was sniffing paint thinner or whatever in my room, they smelled it. So I would hide in my closet in my little bedroom and put sheets up. I knew that wasn’t right, but I didn’t sniff the glue or the turpentine or the paint thinner or whatever to get messed up. At that time, I didn’t. I didn’t do all that to escape reality. I didn’t know why I was doing it back then. But through the years, I found out that, when I did alter my brain with these chemicals, I was actually able to look myself in the mirror and make eye contact. I was okay with myself. My dad convinced me every day that I was a worthless piece of shit and that I was never going to amount to anything. But when I altered my brain with those chemicals, I could like myself.

That’s the way my childhood was. I had a sister who I wasn’t close with. We didn’t become allies through our growing up time. My dad did the same thing to her, but he mostly focused on me.

Every time I’d had enough, when I couldn’t take any more of what my dad was calling me, I would come in and cry to my mom. I would say, “He called me “motherfucker” again,” or whatever.

She would say, “Oh, Guy. You know your dad’s sick. He’s got diabetes and he’s on a lot of medication. He doesn’t know what he’s saying.” She would make excuses for him.

They both went to the VFW to drink a lot. There was a pool outside, so there was an automatic babysitter. Me and my sister would swim in the pool all day while they were in there getting hammered.

One night, on the way home, they got into an argument. It continued once it got into the house. My dad ended up beating the shit out of my mom. Later that night, my dad woke me up and told me to come in the living room where my mom was laying on the couch. You could tell that she was pretty well beat up.

My dad was yelling so loud. I was deathly afraid. Deathly afraid of him. I don’t know if I thought he was going to kill us, but I knew that when he got like that, he couldn’t control himself. Or he didn’t control himself.

He yelled to me, “Who do you want to live with? Do you want to live with your mom or with me?”

I mean, I’m a kid, a teenager, and my mom’s looking up at me with these puppy dog eyes, and my dad’s glaring at me with his false teeth chattering. I said, “Well, I want to go with you, Dad,” because I was scared he was going to beat the shit out of me.

My mom gave me this glare, and he says, “Now, there you go. What do I do?”

The next morning, I walked out and Mom was still on the couch. She says, “You little son of a bitch. Why did you tell him you wanted to go with him?”

Now, I had no idea what love was like in my family growing up, other than seeing other people experience it. By this time, I was getting ready to graduate from high school, and I was drinking pretty heavily. I couldn’t keep a job when I graduated. I partied too much, and night shifts didn’t work because you go into work drunk or whatever. Or, if this is mid-shift, you have to walk by a bar to get to work and that interferes. Anyway, couldn’t keep a job, so I thought, “I’m just going to go into the military.”

I got drunk and drove to Kansas City. I walked into the recruiting office and took an ASVAB test.

He said, “Well, you qualified for everything except nuclear power,” and one other thing. I can’t remember what it was. He said, “What do you want to do?”

I said, “I don’t know. What do you got?” Just like that. Punk ass kid. Didn’t know anything. Just needed to get away from my house before something bad happened.

He goes down the list and he said, “How about submarines?”

I thought, “That sounds cool, being in a submarine,” so I picked that.

When he got down to what I wanted to do in the Navy, he said, “You could be a torpedoman.” My dad was a mine specialist in the Korean War. I thought that was pretty cool. As much as I hated my dad, I thought, “Maybe I’ll have one more chance of making him proud of me,” so I became a torpedoman in the United States Navy, in the submarine service.

Partying was condoned with the exception of drugs, because alcohol’s not considered a drug. I partied hearty, became a very good sailor, and rode two different submarines while I was in the Navy. My career was going places. Fast tracking and sending me to weapons schools left and right. I was on the first submarine to certify the Tomahawk cruise missile peacetime, and that was a big deal back then.

I used to not like partying on the base, so I started driving about thirty miles to El Cajon or Santee, California. One night, I was in this really, really classy joint called the Kentucky Stud. I noticed this guy. I went in there for weeks on end, and pretty soon, this guy came up to me after the bar was closed. We were in the parking lot and he says, “Do you want to go to the park and party?”

I said, “Sure.” We got over there, and he broke out some methamphetamine. I was so drunk that I said, “Yeah, let’s do some. I’ve never done it before.”

He pulled it up in a rig. The first time I ever done methamphetamine, not only did I do it with a needle, but I didn’t do it with my needle. I let him shoot me up, and I don’t know if the needle was ever used before or not. Without knowing anything about AIDS and hep C and all this stuff.

I knew that particular night, after it was over, that I liked the meth—but I never wanted to use a needle again because I couldn’t control myself, so I started snorting it.

About three or four weeks later, I was in the Kentucky Stud again and I noticed this guy was staring at me. I was getting a little creeped out about it. I thought, “What’s this guy staring at me for? Look at all these women.” I walked over to him. I said, “Are you staring at me?”

He goes, “Yeah, what of it?”

I said, “Well, I’m thinking we need to talk about this.”

He was testing me. He was a local dealer and he wasn’t a trashy dealer. He lived in an upscale community and he needed to protect his investment, if you will. So, I got hooked up with Bob. Bob thought he could trust me and he put me through a few tests. I didn’t even know they were tests at the time. That went on for close to seven or eight months. I would go out to sea and that’s the only time I wasn’t doing meth. When I’d go back in port, it was on.

One night at the Kentucky Stud—nobody ever went out to that classy place—I saw another guy off of my submarine. He saw me doing some meth. The next day when I came into work, everybody was lined up to do a pee test. Of course, my pee test came back hot. I had a court martial.

The judge told me that I no longer could be on submarines, but they’d invested way too much money in me and I had a good career ahead of me. I just couldn’t have submarines. I told him right then that I love submarines and if I couldn’t have them, they might as well just throw me out right now because I’m going to go AWOL again. It took me two more times of going AWOL before they finally gave me a bad conduct discharge—which I didn’t know, in seven years, was upgraded to honorable under general conditions.

There’s a few more stories in between there. During that time, my first tour with the submarines, I got married at a very early age. She got pregnant. We had a baby girl. When our daughter was one year old, I was still so hooked on the meth. I just knew things were falling apart. I couldn’t do home and drugs at the same time, so I’d choose the drugs. I went into the house and said goodbye to my wife. I kissed my one year old daughter goodbye and I left. That was it.

When I got in trouble with the Navy, I had to do ninety days in the brig once I was [done with] that final court martial. Ninety days in the brig and then discharged. During that ninety days, I got sobriety back again. I got in really good shape. I knew on that ninetieth day when they let me out: if I go back, I’m just going to go back and use again. I got the money that I had coming to me, and I got my little red bag. I went to the gym and got my stuff, got a cab and went to the airport. I walked down the line until I saw Kansas City and I bought a ticket.

I called my cousin and told him to meet me in Kansas City at midnight. I said, “I’m coming home.” He did, and I stayed at his house that night. I didn’t want him telling my mom and dad. Next morning, I walked into my mom and dad’s house and I said, “What’s a guy got to do to get a good breakfast around here?” Of course, it was a reunion. Mom and Dad both crying and the whole thing. Their son’s alive, because the next phone call, they were worried about their son being dead.

I gave up the meth for a while and moved to Topeka. Found another lady. Of course, I’d been divorced from the first one. Met another lady, Donna, who happens to be my son Chris’s mom. She lived in Topeka, and I started hanging out with her brother. Her brother was doing the meth the same as I had been in the past. He introduced me to this other guy, and then it was on.

Me and this other guy, Kenny from Topeka, we were inseparable. By this time, Donna’s pregnant with Chris and I’m carrying one gun at all times. Not only do we have to distribute this stuff, we have to go out where it’s made and check on things, and we never know what the deal is. Now I’m in the world of paranoia, the vortex of methamphetamine. I started doing opioids at the same time to come down.

That went on for a while. I’m not sure how long. Almost got caught a couple times by the undercover guys, but we were always one step ahead of them. Back then in the middle 80s, there were only three undercover cops working the drug task force. They always traveled together, so as long as we had two different vehicles, they never knew which vehicle for sure. If they stopped one of us, it would be a fifty-fifty toss whether we had drugs. We never had drugs in both vehicles at the same time.

It got to the point where I wasn’t sure what was going on, so I started carrying two guns. We also got a police scanner. All of us had 200-channel, programmable police scanners. I was carrying a .357 and a backup on my ankle, a five-shot .44. We started not associating with anybody but our small group.

That life went on for a while. Donna knew that we needed to get out of Topeka, so we went to Colorado. I thought, “This is another new start.”

It was geographical was all it was. Those snooty people in Vail, Colorado didn’t even know what methamphetamine was. They just did cocaine. Here was when I started driving from Vail, Colorado, making those twelve-hour runs in the middle of the night, going back to Topeka to pick stuff up and bring it back, then doing my end through Grand Junction, Colorado and back. I tried not to shit too close to my house. You know what I mean.

Things started unwinding. During this whole time, I had a locksmith business. Two of them. I was good at home security systems. I was good at lockouts. I was good at installations of keypads and deadbolts and all that. But I got to the point where I just couldn’t do that anymore because I was too busy with the drug world.

After I’d moved to Colorado, there were a couple times I came back. The violence had escalated in Topeka to the point where you really just never knew what you were walking into. I knew that, any given day, it could be checkout time. I was okay with that. I never thought my best friend would be the one who shot me, though.

Kenny’s girlfriend, who was very jealous of all the time that he and I were spending together, told Kenny that I had come onto her and that I tried to pick her up. I went into a bar one night. The doorman saw me and grabbed me by my hair—when I had more. He held a .32 to my neck and he dared me to move. Kenny kicked everybody out of the bar because, by this time, Kenny owned the bar. He sat back about ten feet and shot me six times with a .22.

When I was being shot, I kept moving, and I saw blood go everywhere, but I kept thinking, “This is bad. I don’t know what’s happening.” I didn’t know at that moment he had shot me with wax bullets, so the bullets never went in farther than maybe three quarters of an inch. The wax, when it hits, the heat melts the skin and folds it back—you bleed profusely but you’re not going to die.

Anyway, it was a bad night.

That’s how my life went south in Topeka. I couldn’t go back there anymore because everybody was freaking crazy. I tried to stay in Eagle, Colorado. Chris was about two, two and a half. That’s when I started becoming my dad with his mom. I’d become very controlling, talking down to her all the time, and nothing she could do was right. The whole domestic violence scenario was taking over.

There were three times that I was physically abusive to Chris’s mom. I’m not minimizing it—I’m saying this is how quick it escalated. The first two times, I may have left a mark on her face where I slapped her or something like that. But the third time, on January 3rd, 1989…

My whole world was crashing down around me and I was sitting in a bar, not knowing what to do. I didn’t have a vehicle to drive. Donna was scared to death of me. I had no money. I was feeling bad about myself, and I couldn’t drink or do enough drugs to hide those feelings anymore. I got to thinking, “I don’t know what’s happening, but I’m just going to go home and see what’s going on there.”

The guy who gave me a ride home from the bar knew that I was in trouble. We were sitting in my driveway, and he said, “Are you sure you want to go in there? You can stay at my house tonight if you want.”

I said, “Nah, I’m okay.” By this time, I had so much methamphetamine and opiates and cocaine in my system that I was like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I didn’t know who I was anymore.

I walked in and Donna was cooking spaghetti. She brought me a plate and Chris was in the middle of the floor. He was about three, something like that, now. Something snapped in my mind, and I was thinking that Donna was having an affair with this guy at her work. I tried to convince her to tell me who it was, and of course, there wasn’t anybody. But in my mind, I was going to make her tell me. I took the plate of spaghetti and threw it across the living room into the kitchen where she was. It missed her, but I followed the plate. I went into the kitchen and started beating her, hitting her with my fist and open hands.

The blood started rolling from her nose, and Chris was crying now. She was such a trooper, going through this experience that I can’t imagine what it would be like. She said, “Please take me upstairs. I don’t want Chris to see this.”

That pissed me off even more because, all of a sudden, I felt more guilty for what I was doing. But I didn’t stop. Chris was still on the floor in the living room, and I drug her through the hallway by her hair. I was hitting her the whole way. We got upstairs and I had her in the bathroom. I yanked a towel rack off and started beating her with that. I almost killed her.

Then I felt so guilty, I thought I would try this victim thing that I heard that addicts do sometimes. I laid down on the bed with this aftershave bottle that I had broken, and I stuck it to my neck. I told her, “No, this ain’t going to work.”

She begged me not to kill myself. I really didn’t think I was going to. I just wanted her to feel sorry for me. That’s twisted, but that’s how bad my mind had gone. I didn’t do anything. She went back downstairs.

I had Chris at the top of the stairs then. That Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde thing… I looked down at him. He didn’t understand what I was saying. I hope he didn’t. But I said, “Tonight I’m going to kill your mother, but don’t worry because tomorrow I’ll get you a new one.”

That’s when Donna knew she needed to get out of the house. The next thing I heard was the door close, and it didn’t slam. She was trying to leave. She went to the neighbor’s house. They let her in and hid her up in the closet somewhere, upstairs in the bedroom.

This was January, so it’s cold in the mountains of Colorado. I made sure Chris was okay and I walked out of the house. I followed the trail of blood over to the neighbor’s house. I knocked on the door and, of course, they wouldn’t let me in.

I went back to the house, put my pants on, and made sure Chris was okay. I walked out and there was an axe laying there with a pile of wood. I picked the axe up. I walked over to the neighbor’s door and knocked on it one more time. They wouldn’t let me in, so I hit it with the axe. The door came flying open, just like you’d see in the movies. Red rum shit.

The lady’s standing there begging me to leave her house. I didn’t know that lady and her two daughters, young daughters, were the only ones in that house outside of Donna. Her husband wasn’t there because they had just moved into that place three days before this happened. Her husband was down in Telluride trying to finalize the closing on their house. I do know that they had a shotgun in that house and they had shotgun shells, but the woman either knew where the gun was or the shells. She didn’t know where both of them were.

In Colorado, they had the “make my day” law, so she very well could have shot me and it would have been over. Everybody would have been the hero, and I wouldn’t have blamed them for doing that.

Anyway, I looked through the house and I couldn’t find my wife, but I did see the two kids peeking over the bed. Little did I know that they were urinating on themselves because they were terrorized so much. I’m glad I didn’t know that because that guilt probably would have fueled more rage in me.

I was barefoot. I walk back down the stairs with this axe in my hand, and this lady continues to beg me to leave her house. I walked into the garage. The garage was concrete, and it was not heated. Now, I don’t know what happened here, whether there was a physiological experience or what, but when I stepped down on my bare feet from the kitchen to the garage floor, on that cold concrete, I came to long enough to know that, whatever I was doing, it was very, very wrong. I dropped the axe, walked out of the lady’s house, and the police came up.

I knew the police. It was a small town. I waited back in the house with Chris. The chief of police came in and he said, “Max, what the fuck?”

I says, “This is bad. This is really bad.” All the time, I’m still trying to think, “How am I going to get away? I can open my screen door, take off running through that field, and then go down through the Eagle River.” Even as twisted as my mind was, I knew that that wasn’t going to work. I asked the arresting officer, “Please don’t handcuff me. I’m not going to do anything. Just take me to jail.” He didn’t handcuff me. He put me in the car and took me to the jail.

My fists were covered with blood, but it wasn’t mine. It was Donna’s. There was a guy behind the counter who I thought was acting all snooty. I put my hands up on the counter, and he said, “Is that your blood? Is that your blood?” I thought he was being a smartass, and I snapped again. I tried to go over the counter to get the deputy. They pulled me off of him and threw me in a padded room until the next morning.

Man, you take a drug addict, you put him on cold turkey in jail, not knowing what’s going on… Honestly, I could not even remember everything that I did the night before. I couldn’t remember. I think it was a good thing. I think the mind is so powerful that it only lets you remember certain things, because if you remember too much, you can’t handle it.

I tried and tried to get people to bond me out and nobody would. This was ’89, so it was a little over two years since my dad died. I called my mom up and I told her if she didn’t bail me out, I was going to kill myself. There’s a good tactic for an addict to use. She said, “Well, son, I hope you don’t do that because I think that’s the only sin that God can’t forgive.” Then she hung up on me.

My mom had to see a shrink after that, and I didn’t know that for years. It hurt her so bad to say that, but having the strength to say that to me saved my life. For the next ninety days I did detox, cold turkey, from opiates, methamphetamine, and alcohol—the whole thing. It was a horrible, horrible experience.

I knew I had a ten thousand dollar bond, but the third day I was in jail, the bondsman came up to me and he said, “You need to quit trying to get your mom to bail you out. I don’t give a fuck if your mom gives me her house, I’m not bonding you out.” This is a guy who was buying liquor at his liquor store and eating at his restaurant that he had. Little did I know that he was saving my life as well. He said, “You’re right where you need to be.”

I had hired a lawyer who was talk of the town. I knew him. He came in on the third day and he said, “Do you have any idea what you did?”

I said, “I remember a little. Not much. I don’t remember doing the things to Donna.”

He said, “Let me help you remember.” He pulled out Polaroids and started throwing them down, showing me where they put her up against the white refrigerator, showing just how swollen [she was]. That’s when it hit me. I wasn’t ready for all that data.

I thought, “I can’t deal with this.” I justified my reason for wanting to kill myself by saying that I had done so many people wrong for so long. I had screwed so many people over. I thought, “I’m afraid that I’m going to continue doing it, so I just need to end this.”

Looking back, I don’t think that was it. At that moment, it was as real as it could be to me. That’s genuinely and authentically what I was thinking in my mind. I needed to believe that. I wasn’t afraid of spending the rest of my life in prison—I was facing seventy-eight years now. They charged me with first-degree attempted murder. They took away the assault charge and did attempted murder, breaking and entering, and the whole thing. It was like, “I just don’t want to deal with this. I can’t.” The guilt just took over.

You remember me saying something about my neighbors being Baptist? I was raised Lutheran. Lutherans are just pissed off Catholics to me. They still drink the wine and communion and stuff, but I never really hooked up and connected with the Lutherans. But the Baptists, I mean, we got into it. When I was thirteen, I was baptized in the Baptist church. I accepted the Lord as my personal savior and asked him to come into my life and take over, but from ages nineteen to twenty-nine, I kind of left him behind.

So I’m sitting in the jail cell now, and I’m thinking, “How am I going to do this? This has got to happen.” They had me on suicide watch, but they left me with my shoelace hoping, I think, that I would just go ahead and take care of it. In the corner of the cell, there was a stainless steel sink and a stainless steel pooper. That’s pretty much all you had outside of your bunk.

Up above the sink, there was a grate for ventilation. The grate was metal and perforated with holes. It was like, a quarter inch thick, and the holes were round. I’m thinking they had like twenty coats of paint on them, so they weren’t sharp edges. How my mind was able to decipher all this, as messed up and twisted as I was coming down off all these drugs, I have no idea.

I thought, “Well, if I take my shoelaces and double them up, intertwine them, I can fish them through those holes and tie them around my neck. I can gently lower myself down from my sink and I’ll kill myself.” At that moment, it was just relief. I found a way to escape and not have to go through any of this. I would not ever be able to do anybody else harm again. All that fractured thinking I was going through.

Right at that moment, when I started taking my shoelaces off… it’s not hard for me to talk about, but it’s hard to describe. I didn’t hear a big booming voice, and there wasn’t a big light come in from outside. It was none of that crap at all. My mind was blank, and I saw three letters, G-o-d. White letters. Capital G, small O, and small D.

I just started laughing. I really did. I thought, “Where the hell did that come from? I haven’t thought about God in years. Why would that now come across?” I sat there and thought for a long time. I wasn’t getting anywhere because my mind was like a pinball, stuck in the machine, bouncing back and forth. Nothing was making sense, and it was just getting worse. I felt myself going crazy. I said, “Okay, alright. I’m not going to ask God to bail me out of any of this mess I got myself into, because there’s been too many times in the past when I made that deal and I didn’t keep my end of the bargain.” At least I was man enough for that.

I said one little prayer. “God, if there’s any reason for me to be on the face of the earth, in the morning when I wake up, let the thoughts of suicide be gone.” A weight came off of me and I slept like a baby that night. I had no idea, coming off all those drugs, how my body would let me sleep like a baby.

When I woke up in the morning, Des, I was the maddest son of a bitch on the face of the earth. I was pissed because the last thing in the world I wanted to do was kill myself. I said, “Alright, here we go. I don’t know where we’re going from here. I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

I knew I needed to get on the phone. I called Colorado West Mental Health, a guy from AA, and a pastor. All three of them came. I called the cavalry, the cavalry came running.

I met this guy, a counselor from Colorado West Mental Health, and I’ve had nobody talk to me before like this man did. This guy was honest with me. He didn’t look at me like I was lower than whale shit. He looked at me and saw the pain, the hurt, the destruction, the addiction, the depression, and the psychotic stuff that was drug induced. He saw all of it. He said, “I got to be honest with you. You know you’re going to go to prison over this.”

That right there kind of allowed me to not try to manipulate the system anymore. For a long time, I was telling myself that I wasn’t going to have to. I said, “This is my first offense other than a DUI that I ever got caught for, and they have the right to give me probation.”

What I didn’t know was brewing in the town of five hundred that this happened in was that the community was taken up. That happened on January 3rd, 1989. January 1st, 1989, Colorado and eleven other states had adopted new domestic violence laws, which saved my wife’s life and saved mine. Those new laws stated that before I could bond out, if I had DV stamped to the crime, I had to go through a violence assessment, a mental assessment, and an addictions assessment. I failed all of them miserably, so I could not bail out of jail. I didn’t know that it also made national news because of the new domestic violence laws. They decided to take my case, because it was so severe, and make a test case out of it. I didn’t know all that stuff was brewing. They wanted to see how these new laws were going to pan out.

After ninety days of being in jail and realizing that I wasn’t going to get out of this one, I owned it. I thought, “Whatever I need to do now. If I have to spend the rest of my life in jail, seventy-eight years, whatever, I’m fine with that. But I don’t want to live like this anymore.”

My attempt, as far as suicide… I don’t know what levels people go through. I think every one of those attempts, at whatever level, is relevant because somebody’s bottom isn’t going to be near as dramatic or catastrophic as this other person. But that’s what it took for each one of us to find the place where we needed to start over. After that ninety days, it got me to the point where at least I could look in the mirror and say, “Yeah, you know what? I’m pretty much a piece of shit. But that’s at least what I have to work with. That’s where I know to start from.”

During the ninety days, my counselor and I had become good friends. He had been trying to get me a place to go to rehab, but everybody was scared to death of me because of the charges. It was all over the news. Nobody would take me except for this one place. It was called ARU, Addictions Recovery Unit, down in Grand Junction. The bondsman agreed with the judge that, if my counselor was able to find me a bed, if I left the jail parking lot and went directly to Grand Junction to check in, they would allow me to bond down. And I did.

That’s where I started learning about shit I never knew about my whole life. I was ready for help. I even went in to my counselor as soon as I got there. I went in to my counselor and started telling her all my manipulative bullshit, things that I do. I said, “Watch me if you hear me say this.” Being that honest with myself felt so good, but I was scared to death.

I spent the next twenty-eight days there. My counselor told me that, before you can start on your recovery, you have to clean some of this stuff up—stuff that you have control over.

She said, “Your father died two years ago.”

I’m thinking, “I hate that bastard. Why would I even consider trying to clean any of that up?”

She said, “Because you’re going to hold onto that resentment. You’re going to continue to use after you get out of here any time you see somebody that looks like your dad or sounds like your dad, or you see somebody being treated bad, and it triggers something. So, let’s just try this.”

I said, “Alright.”

She said, “What I want you to do is go back to your room and write your dad a letter. Tell him everything. The good, the bad—everything.”

I had about four days to do it. On the second day, it’s like I couldn’t put anything down. But as soon as I sat there and wrote “Dear dad,” the tears started flowing and I was able to write everything. It wasn’t enough just to write it. I had to go in front of my group and read it out loud. Then I tore it up and threw it away, symbolizing letting go of it.

That’s what I went through for the twenty-eight days. Falling off a boulder and letting people catch you while you’re blindfolded. Mountain climbing while you’re blindfolded, and you have to trust this other person to tell you where to put your foot or your hand.

I had a really good first twenty-eight days. Then they allowed me to stay out on bond and also allowed me to go back to Kansas. I stayed with my mom, and I started going to AA. I soaked it up like a sponge.

For the next eleven months, I was out on bond, but I had to make ten bond appearances back in Colorado. Like once a month, I had to drive back. Every time I drove back, the district attorney attempted to put me back in jail. I thought about how I was going to take him out. Then I prayed for him. I didn’t pray that the bus ran over him. I prayed that he would lose the hatred he had in his heart for me.

After eleven months, everybody saw that I was making an honest change for myself, so they were willing to do a plea bargain. Of course, Donna had to okay everything. I ended up having two felonies. I pleaded to first-degree burglary and second-degree assault, and they were two five year sentences to be served at the same time. To make a long story short, as far as my jail stuff goes, it was the best thing that ever happened to me.

Some really good experiences in county jail, then I got sent down to state prison. I didn’t want to, but I worked on a wild horse program making two dollars a day. They would take these wild mustangs, round them up and bring them in, and put them in this two hundred-acre place. We had thirty-five to forty days to work with these horses and get them ready for adoption, if they were at all capable of being adopted.

These horses were ten times more afraid of me than I could have ever been of them. They were out there alone in the wilderness for years, and all of a sudden, they’re rounded up by helicopters. They get freeze-branded and get stuck in this semi, and they get shipped off to us. They’ve only seen ten or twelve humans their whole life. Now they got some human wanting to walk up to them, and they were scared. The lessons I learned from the experience of being on that horse program led me to understand, on a deeper level, that everything happens for a reason. Trust and patience is what I learned from those horses. They taught me more than any man ever could have at that point in my life.

Let me finish with when I got out of prison. I had two five-year sentences to be served at the same time. I did two-and-a-half years—something like that—twenty-three months is what it was.

I had some lady, clicking her heels, coming down the hallway. She said, “Your parole board is in twenty minutes.”

I said, “What?”

I went and sat in front of the parole board. They said, “Mr. Maxwell, could you please tell us what happened on January 3rd, 1989?”

I just said, “Listen, I’m not trying to be an asshole, but you have all that stuff right in front of you, and I don’t know what I could add to that.” He said nothing. They’re all in their suits and the women are dressed up. I’m thinking, “This is going through the motions,” so I told them.

They said, “We just want to hear it from you,” so I told them. Then I went back to my cell. Half an hour later, the lady came back and said that I was going to be paroled.

It was, like, the day before Thanksgiving, I had a plane ride going from Colorado Springs to Kansas, and Donna and Chris were going to be there to pick me up. Chris came running up to me, and he said, “Daddy’s not mad anymore.” Broke my heart, but I held it together.

Donna and I spent a week together, just to see if there was anything. At the end of the week, she looked at me, I looked at her, and we just smiled. We knew it wasn’t going to work. But from that moment, we were best friends. We tried it. There was way too much water under the bridge on that one. Too much baggage, too much damage. She’s still my best friend today. One of the great things that happened to Chris is that she never talked shit on me, and I absolutely had no reason to talk shit on her. We just worked together, from a distance, at being the best parents we could be.

In my early recovery, Chris and I would hang out. We would go to a flea market and then go to a recovery meeting somewhere. We would go to a yard sale the next day, and then we would go to a meeting. I had no idea that what I was doing to that young man. I knew I was doing what I needed to for me. If I didn’t set up really clean, tight, and concise boundaries around my recovery, I wasn’t going to be good to anybody else, so I just continued doing what I needed to do to grow. That meant dragging him along everywhere I went. With him sitting in all those recovery meetings, I didn’t know it was impacting his life like it did.

I traded in the drugs, the heavy alcohol use, and all that. I took up mountain climbing. For ten years, I climbed the mountains of Colorado. It was my church. Standing on top of a fourteen thousand-foot mountain and looking out, my shit looks pretty insignificant in the big scheme of things. That’s where I went to go to get my perspective again.

I started doing volunteer work. For fifteen years, in some form or fashion, I did volunteer work. I had the opportunity to work with Michael Bolton. Every year he puts on a gala in Connecticut for at-risk women and kids. I volunteered to go there one year because he had heard of what was going on in the domestic violence world and that there was somebody out there who was actually a recovering perpetrator, recovering abuser. He was talking about it, and going to government events, talking to government officials and law enforcement agencies and all this, so I had the opportunity to go out and hang out there for a while.

When I went to North Carolina, I had fifteen years of recovery under my belt. North Carolina was actually willing to say that they needed help. We had this program called Peer Support Specialists, and I had never heard of that. It was a glorified name for people who were really screwed up at one time and still working through it. I was in the second class ever of North Carolina Peer Support Specialists—second graduating class.

I mean, somebody with two felonies, how do you do a resume? I kept a binder. Every time I did something and it was printed in the paper, I’d cut it out and put it in what I called my “I love me” book. I didn’t know what else to call it. So, when I went to North Carolina, I took fifteen years worth of newspaper things and working on a project in Kansas City back then. They took one look at that and hired me on the spot.

I did Peer Support Specialists for three and half years. I studied to get my Certified Substance Abuse credential. I moved on to get my co-occurring disorder credentialing. Then I got into the world of suboxone and methadone, and I also had a credential for medication-assisted treatment counselor.

Here I was, a guy with two felonies, working for different agencies in North Carolina, going into people’s houses and talking to them about addictions and domestic violence. At the same time, I was running one domestic violence intervention program and co-facilitating another, as well as running an intensive outpatient program for methamphetamine users—a matrix program. I had actually immersed myself into the world of recovery at a level I had never understood.

But trying to get all these credentials costs a lot of money. I didn’t have money. So I used my skills as a kid and worked for free. I did one forty-hour job that I got paid for. These other jobs, I just gave them my time and they gave me their supervisory sign-off where I needed it. I needed seven thousand hours before I could get my credential. It wasn’t a long time at all before I got seven thousand hours.

After that, there were some things going on in the mental health world and the substance abuse world that were too political, and I thought maybe it might be a good opportunity for me to get out, move back to Kansas, and be a dad to Chris and a granddad to his son. So, I did. I moved away from North Carolina. I moved to Kansas, back to Atchison. One of the worst things I ever did.

It wasn’t because of Chris or my grandson. It was because I was moving back into the world of retail, working at O’Reilly’s Auto Parts for ten dollars an hour. I was trying to make it on ten dollars an hour in a house where I was paying three hundred and seventy-five dollars rent a month, plus utilities. It was hard. It was very, very difficult. Robbing Peter to pay Paul, not knowing who’s going to get paid this week. That’s just financially.

The other part of it was that my hometown had been taken over by drugs. I saw what addictions had done to people who were my age. Here I was, standing behind the counter, and they come crawling in with a walker, or they’re not there anymore. The methamphetamine was horrible.

As far as the retail world goes, if you see somebody stealing something off the shelf, you’re not even supposed to say anything to them. They just write it off. I didn’t know all that. I had a hard time working with some folks who weren’t involved in actually working anymore. They just showed up to get their hours, yet all this stuff has to get done.

I started getting pretty depressed. After being in recovery for that long, I knew that I was getting in trouble. The first thing I did was call my son. I asked him, “Are you going to be alright if I move back out to Colorado? A job opening came up. They want me back out there and I’ll be making really good money.”

He said, “No, Dad, I love you. You do what you have to do.” Wouldn’t expect anything else, but at least I had to ask him.

Two days after I put in my notice at O’Reilly’s Auto Parts, I got a call out of the blue from a guy I used to work with in North Carolina. He was the director of the substance abuse facility, the methadone clinic, that I worked at as a counselor. He was my boss, and had left that facility to come to New Mexico. He had an opportunity to be the executive director of five facilities, four here in New Mexico and one in Colorado Springs. Out of the blue, he called and asked me if I was ready to leave Kansas yet.

I said, “Why?”

He said, “I want you to come to Albuquerque and be the director of a clinic I have down here. It’s a pretty good place.” We talked for a little bit. I really didn’t need to think about it too long. I knew that this was where I was supposed to be. This door opened up for whatever reason at this particular time. It wasn’t an accident.

It wasn’t even a week and a half later, Des, because when I left North Carolina, I just took what fit in my car. These guys here in Albuquerque were paying for my move totally. I went and got a small U-Haul truck and put my car up on a trailer. Whatever I had, I put in the ten-foot truck, and I drove out here. They paid my way, put me up here for a couple months until I got on my feet, and then they paid me well to run this program.

That’s how I ended up here, almost twenty-eight years later. January 3rd, I’m thinking it’ll be twenty-eight or twenty-nine. I’m not even sure anymore, but that’s my story.

Des: That’s quite the story.

Guy: Yeah, you hear them all the time.

Des: They’re all special.

Guy: Yeah, you know that. You know that.

As far as the part about being able to maintain self-care in a world where you’re working around people who are on the edge of death at any given moment, I had to find out the hard way.

The first time I had a client die, I heard it on the phone. I got a call on my phone, which I had shut off that night because I wasn’t on call. The next morning, I listen to his girlfriend shouting over the phone, “Hank’s dying! Hank’s dying.” I can hear him throwing up in the bathroom in the background.

He had varicose veins in his neck. He was drinking raw alcohol in North Carolina and one of his blood vessels blew up. He was choking to death on his blood and throwing up in the bathroom. And this guy told me he was going to die.

His dad is a prominent businessman out of Atlanta, Georgia. His dad told him, “You got all the money in the world. All you have to do is not drink or use drugs for a year, and you can start having the money in the trust.” But he didn’t want to do it, and he couldn’t do it.

I felt so connected to that particular client because I knew he wanted it, but he couldn’t figure out how to want it bad enough. He was the first guy, after we’d been working together a while, to say, “I wish I could see what recovery was like out of your eyes for thirty minutes, and maybe I would want to quit forever.” Those kind of things.

When he died, I took it hard. It was my first time I had a client die like that. I was questioning if I was even in the right field. I was questioning if I did everything I could have. I was questioning if I had any part in his death. Somehow, I had to make it about me. I was trying to see if I had said anything wrong, or led him on, or if there was something I could have said differently, or… I was driving myself crazy.

I told myself, “You know what? I’m not going to be able to stay in this field. I’m going to burn out if I continue to think that, because there’s going to be a lot more people who die.”

I adopted a way of working with folks that allowed me to realize that, as they had their hand on the doorknob, this very well may be the last time I see this person. So, I’m going to turn around, and if there’s anything I need to say or want to say, now’s the time, because we can deal with this now.

That’s how I keep from going insane when people die.

Des: That’s hard.

Guy: Questions?

Des: I’ll ask you the question I ask everyone, even though I’m pretty sure I know the answer: is suicide still an option for you?

Guy: Absolutely. Every day. So is sticking a needle back in my arm. If I ever forget January 3rd, 1989…

Okay, here’s the way it was put to me: the closer I come to forgetting January 3rd, 1989, the closer I come to doing it again. I need to keep it green. I need to remember, not because I want to relive the horror. Not because of all that bullshit, but because I’m no different than anybody else. That’s why the four hundred and some clients there love me as the director. I’m not the snooty ass director who walks through and thinks I’m better than everybody else.

I walk in and say, “I was homeless, too. And you know what, here’s what you guys need to hear me say. I’m the director of this program, and by the grace of God, here I am. I have a high school diploma. That means I had to do everything three times, differently and hard and backwards, go around the barriers and dig tunnels underneath them. But I had the desire and this is what I wanted to do, so I did it. If you want something bad enough, you can get it.”

I learned a lot from a guy by the name of Zig Ziglar, who has passed away now. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of him or not.

Des: The name sounds familiar.

Guy: He’s a world-class motivational speaker, but he was broke at forty. He started started going door-to-door to sell not Tupperware, but cookware. His gift of gab and genuine authenticity opened the door. He did become a multi-millionaire, but that wasn’t his goal. He took his gift of teaching people and made it international, worldwide. I actually got to meet him.

What I’m saying is, during my recovery time, when I wanted to do something—if I wanted to do it bad enough—I had to find a way to do it. I saved up four hundred bucks for the VIP ticket to go to Denver and spend a day with these people. Mikhail Gorbachev, Fran Tarkington, Elizabeth Dole, all these people. Then, of course, Zig Ziglar. I had breakfast with him.

The reason he became a hero to me… I was not very good at reading. ADD. Read a paragraph four times over and not even know what the first sentence said. But during the time I was in jail, I dealt with it. I read some of Zig Ziglar’s book. One quote that I live by still today, that has been my mantra is, “You can have anything out of life you want, as long as you help enough other people get what they want.” That meant a lot to me.

Chris turned out pretty good, too. Been my hero for a long, long time.

I was sitting in a panel of experts at a seminar one day in Kansas City. It was put on by the Kansas City Bar Association. It was a thing about the effect domestic violence has on kids. On this panel of experts, there were six women and there was me. I was the only male. Back then, I was pretty much the only guy who was willing to stand up and talk about what he had done to his spouse and how he treated and objectified women through his life. I don’t even remember her name, but a prominent judge who everybody knew [was there]. This lady asked me, “How does it feel knowing that you can never use drugs again?”

I said, “Ma’am, I really need to be completely honest with you. I don’t know what that word “never” means. It kind of scares me to death. All I have is twenty-four hours. Today, when I woke up, I agreed and made a deal with myself that I wouldn’t use drugs for the next twenty-four hours. I don’t know about tomorrow. I really have to keep my life simple. I have to take it in chunks and break it down to where I can understand it, because if it gets to the point where it gets too confusing, I don’t know what’ll happen. I can handle a day at a time.”

One example of how sick my mind was when I was getting ready to leave treatment in Grand Junction: There’s a saying in recovery, “Ninety in ninety.” Ninety meetings in ninety days.

I hadn’t heard that yet, but maybe once, and this guy just says, “Ninety in ninety.” I swear to God, what I heard was, “One hundred and eighty.” He saw the fear on my face. I was just getting ready to leave and this guy throws that shit at me. He goes, “Whoa, whoa, wait a minute. One meeting a day.”

I said, “Oh, alright, I got that.”

That’s how I’ve had to live my life. That simple.

Des: What did it feel like going out there and being the one guy who could own that? How much of other people’s hurt did you have to take on? How do you deal with that? Because you do it every day, don’t you?

Guy: Yeah. I knew that I was left on this earth for a reason. When it’s my time to go, it’s going to be my time, but it’s not quite yet. For the last twenty-eight years, I made the agreement with myself that I needed to change how I live, and that wasn’t very easy to do. Giving up the drugs was kind of the easy part. After carrying guns and police scanners around for so long, it took me probably three years of one-on-one therapy to help me rewire my brain to get the color coding back to where red’s with red and white’s with white, because of the learned behavior from my dad and me taking it to the next level of becoming a violent person. That’s what took the longest for me.

With that being said, I got hired by a company out of Kansas City to go around the state of Missouri to do eight-hour seminars in a different location each day, with highway patrol, state officials, officers—all law enforcement. There’s probably a huge amount of domestic violence that goes on within law enforcement that never gets reported. I experienced some of that, myself.

One day I was talking behind the podium. I was telling my story and it was making several of these officers extremely uneasy. They would start moving, they would touch their badge and their gun. Their faces would be getting red, I could see the veins starting to come out, and they were just giving me the glare. I knew that I wasn’t doing it to get that reaction, but if that reaction was what they were experiencing, good. Maybe, just maybe, one person out of all those men who really wanted to shoot me that day but they couldn’t, didn’t go home and beat their wife that night.

The day after I was sentenced and went into jail, I picked up the Vail Valley Paper, Eagle Valley Enterprise, and the headline said, “Wife beater draws five years in prison.” Wow. That was written about me. “Wife beater draws five years in prison.” I had to live with that. Ten years later, the same lady, ran another story. “One success from the justice system.” Both of those articles were written by the same lady because everybody in that community was keeping tabs on what I was doing.

While I was in jail, I was asked to go to Beaver Creek, Colorado, to talk to big name people with deep pockets who do donations to organizations like Colorado West Mental Health. I was getting ready to get up on the podium and tell the audience how much Colorado West did for me, trying to get money to continue the jail program and all this.

This little, tiny lady came up to me. I guess she knew Donna and knew about that night. She may have even been there at the hospital. She came to me and said, “I hope something really bad happens to you while you’re in prison because I don’t think you even deserve to breathe the same air as I do.”

Then I had to go out and give that talk. I learned how to deal with these things, knowing that I was going to take a lot of punches, but I was also going to be okay with that. I had to be okay with it, knowing that I’m going to help a lot more people, hopefully, than take punches.

I don’t care if somebody wants to judge me because of what I did back then. I’ve already forgiven myself. That was the hardest thing for me to do. To forgive myself for even thinking about taking my own life. Well, shit happens. You never know.

There was one other time that I honestly thought I needed to check out. I was in a house full of guns. It was a thirty-second thing, and it was gone. I knew where all the guns and ammo were, but it just wasn’t the right thing to do.

Des: So, the suicidal thoughts didn’t necessarily stay away after that night.

Guy: No.

Des: You still have them?

Guy: I haven’t. No, I haven’t. I know it’s an option. Who was it… oh, shit. Who’s the guy who wrote Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas?

Des: Oh, Hunter Thompson.

Guy: Yeah. You’ve seen the show on him?

Des: No.

Guy: You got to see it, Des. Days before he killed himself, he’s in the kitchen—it made total sense, if you can understand what he’s saying because he’s got the cigarette hanging out of his mouth. He said that the thing that keeps him alive is knowing that he can take his life at any moment. It’s like an insurance card, you know? People who are really trying to quit smoking cigarettes, they’ll have one cigarette and leave it in their pocket just because it’s there. They’ll freak out if it ain’t there.

It’s always an option. So is going and using again. Look at where I am, for Christ’s sake. All I have to do is call one of my clients into the office and say, “Hey.” I’m very aware of what that looks like on other people. I can see it. I’m sure the same way you can. It’s there. I think it’s a gift to be able to recognize that in somebody and not be afraid to address it. So many people would be afraid to do anything.

So, no, I haven’t. Twice, I’ve actually ran the idea. One, yeah, it was going to happen. The other one was thirty seconds. That’s pretty much it on that.

Des: What do you do on the bad days?

Guy: I have a spiderweb network of people in my life who are strong throughout the United States, and they’re one phone call or text away. The thing I have done through the last twenty-eight years is that I never lose my gratitude for the people who were there for me. Every year, year and a half, I’ll take a handful of people who helped me and I’ll look them up. I’ll thank them in person or on the phone.

The police officer who arrested me did much more than just treat me nice. He also gave the most grueling testimony in front of the judge that I could have seen. I mean, he was telling the truth, but he was honest. He was saying things like, “It’s the worst case, the most bloody crime scene I’ve ever seen. The only thing missing was the dead body.” That was honestly what he felt. I just got off the phone with him a couple weeks ago. I call him every couple years, and I thank him. I give him an update on Donna and Chris and me, because people need to know.

One time, I called up and I got a hold of his wife. She said, “I’m so glad you called.”

I said, “Why, what’s going on?”

She said, “I think Phil’s thinking about taking his own life.”

I said, “What? He was the cop that arrested me, for Christ’s sake.”

His kids suffered from mental wellness issues. His kids have kids—his grandkids—and they suffer from the same thing. Well, Mom and Dad can’t take care of them, so it’s up to Grandma and Grandpa now. Asperger’s and some other things going on that are very, very challenging.

Phil was struggling. Big time struggling. So [his wife] gave me the desk number to his phone at the police station and I called him up. I didn’t let on that I had talked to his wife about this. I just did my normal thing. I said, “I need to remind you something.”

He says, “Yeah, I know. Because of what I did back then, you’re alive, and your son and everybody was treated [well].”

I said, “You really know how much that means to me, right? Because each one of us have our own stuff that we’re dealing with. You never know what kind of connection you’re going to make when you make a phone call like this. I have no idea, Phil, what you’re going through, but you’ve always been there for me.”

Then he said, “Wait a minute.” He shut the door, started bawling, and told me the whole thing. The roles were reversed and it was my turn to help him.

That just came out of me doing my gratitude thing that I do every couple years. I even called the prosecuting attorney, who I finally found. He is an attorney in Denver now. I got ahold of his secretary and I said, “Could I please talk to Mr. Bennett?”

She said, “Who’s calling, please?”

I said, “Guy Maxwell, and he ain’t going to remember.”

She came back and said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Maxwell, he’s not available right now.”

I said, “Okay.” Then my heart’s like, “I need to talk to this guy.” I called back about twenty minutes later. I said, “Listen, this is Guy Maxwell. I need to tell you something. I’m not calling for any other reason but to thank that man for saving my life. I need to tell you, because if he had not put first-degree attempted murder on me, I would not have taken my charges seriously, and I would not be here. I’d be dead.”

She said, “Hang on.”

Then he got on the phone with me and, for the next forty-five minutes, I told him. Everybody knew the situation from 1989, but they didn’t know what all happened.

I popped back through Colorado to go on vacation here a month or two ago. A lady on Facebook who was working for the district attorney at that time asked me if I would come back to the jail where I thought about killing myself and talk to a group of people. So, for the first time in over twenty-something years, I went back into the Eagle Colorado Jail and did my thing. This time, as the director of a substance abuse facility, not somebody who’s facing seventy-eight years in Colorado State Penn.

Now she wants me to come back and talk to the whole jail population and the drug court they have now. Opportunities keep opening up by me reaching out and thanking people who were there for me.

Des: If you could address the people reading your story, is there anything you’d want to say to them?

Guy: Just remember that, if you choose to even contemplate taking your own life, remember it is a choice. It’s an option. If, in that moment, you’re actually thinking about that option, please try to realize that it may not be the most clearest moment of the day for you. Don’t be afraid. Please reach out and ask a friend. Ask somebody at the bus stop. Ask somebody to talk to you for a minute. Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask for help. Just don’t sit there alone. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Thanks also to Alison Rutledge for providing the transcription to Guy’s interview, and to Sara Wilcox for editing.