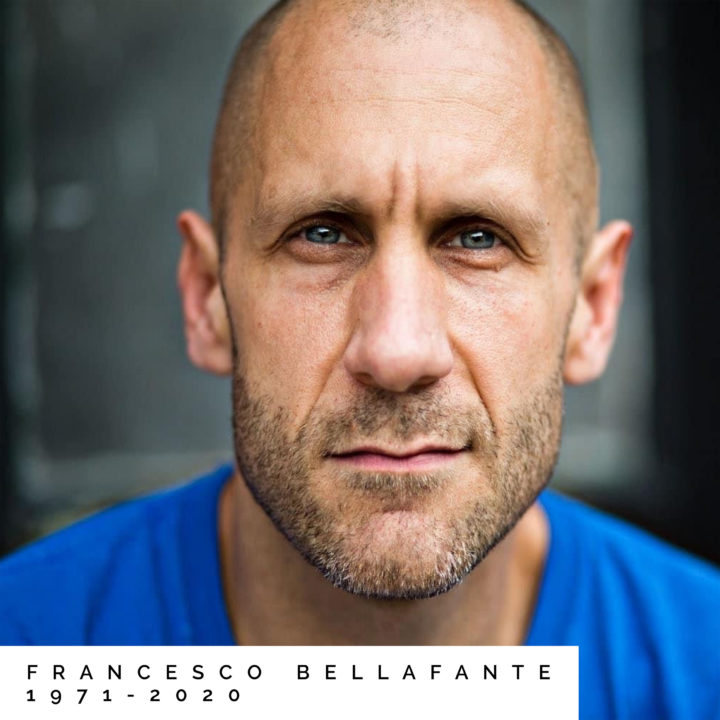

Remembering Francesco Bellafante

In Loving Memory of Francesco Bellafante

Francesco Bellafante took his life on November 16, 2020. He worked at the intersection of suicide prevention advocacy and information technology, and he cared very much about helping suicidal people. He wanted better for us, and he pushed toward that end. When I think about the folks we’ve lost in the Live Through This family, I think about all the hurt they endured and all they did to survive. I think every day we choose to stay is a triumph. I know Francesco was failed by the system in these last months, and I hate that he felt he had to go, but (and mainstream suicide prevention wouldn’t want me to say this) I hope he’s not in pain anymore.

Francesco was 45 when he shared his story with me in Philadelphia on August 11, 2016. His story remains on the site because he was a member of the Live Through This family. Even though he’s gone today, his story remains as an important reminder that, as suicide attempt survivors, we are each still at risk for death by suicide.

Please read this story with care. If you’re hurting, afraid, or need someone to talk to, please reach out—to anyone, anywhere. Someone will reach back. Please stay. You are so deeply valued, so incomprehensibly loved—even when you can’t feel it—and you are worth your life. —DLS, 12/29/20

I think, really, the foundation for the suicidal behavior that I experienced when I was 26 into 27 was laid very early, in my good fortune. I was, and I am, very lucky, very fortunate. I mean, not my happenstance of birth. I mean my genes. I mean the wet stuff between my ears. The things that you do growing up.I think I had great parents who, as far as apples and trees go, the right values were given to me and fostered within me. Again, this good fortune and good luck I had, with the exception of a struggle with being unhappy about my physical appearance as far as how much I weighed, I didn’t really have any significant problems growing up. I had no major traumas, I had no abuse. From the experiences that I’ve had, I had a relative cake walk. I’m blessed. Very fortunate.

Even more nail on the head, I think at the base of my suicidal behavior was a lack of experience with adversity and failure. If I decided I wanted to do something, and then set about doing it, I did it. My parents told me what to do and I did it. They thought that I was good, they saw me as good, so I saw myself as good. I went to school. My teachers told me what to do and I did what they told me. I did it well, and they told me that I did it well, and I felt good.

Then I graduated from school, and it’s like, “Okay, what do we do now? Oh, I should get a job. Okay, I’ll get a job.” I wasn’t sure which job to get, and I thought, “Okay, maybe I’ll just do what my brother’s thinking of doing,” so I did that. I kind of took his passion and followed that, and I found somebody else to tell me what to do, and they were clear. They said, “Do this,” and I did it. I did it well, and they told me that, and everything was good.

At 26, I was in the top five, ten percent of three hundred and fifty consultants. I worked in Manhattan, a couple blocks from Wall Street. I was the youngest person out of three hundred and fifty who got a title.

I was assigned to a project in Canada where I did not know the subject matter. I worked in finance, but that’s like saying you work in medicine or law, right? It’s ginormous. I ended up on a project that was being run by a competitor, by a competing consulting firm. I think there was a board member from the bank who had gotten one person from my company on the team. That was me. I was the only person under 30 on a seventy-person team. The field was commercial lending. I knew what a loan was, but I knew nothing about what banks did, the systems to do that.

I’m in the first breakout sub-team meeting on this project. There are seventy people on the project. You’ve got seven teams of ten people each. I’m the new guy, so you’ve gotta go around. We all say our hellos. It gets back to the head guy. He’s the client now. There’s the consultant over here, and there’s the client—he’s right here, I can still see him—and he asked me a question that I didn’t even understand the words in, because he used lingo from commercial lending.

He asked the question, [something like], “Do you have experience in, and can you help us out with blah blah blah blah?” Maybe he said—and the way I’ve written it is—commercial lending risk scoring systems. He probably said something like that.

I did not know what that was, and I knew that the answer was, “No, I don’t have that experience,” but in the moment, I don’t know, I got small. His expectation was for me to say yes. I couldn’t lie, ‘cause I couldn’t fake it. He is not much further from me than you are, and when he was done asking the question, I said, “Excuse me?” as if I didn’t hear him. I know the blood must have just fallen out of my face.

He didn’t stutter, and he’s three feet away from me. He slightly rephrases the question as I summon the courage to give the answer I know to give, which is, “No, Doug, my experience is actually in this. What I’m really an expert in is people processing technology…” Some business bullshit. I readied myself to say that answer, and I said it and then, I’ll never forget, the competing company team lead, the consultant, he rescued me then. He was like, “Wow, that was really awkward for this kid, right?”

That was the beginning. That was it. That’s what started it.

The theme that I’m pulling out here is, I think, for my whole life up to that point, I was a human doing, not a human being. How I felt about myself is how the people that I associated with, was in contact with, thought about me. It was my job to keep how people thought about me good, to make them think well about me, think good thoughts about me.

This was an instance where it was evident to me that that was not the case. I don’t know. I’ve never spoken with anybody from that group, and I eventually wriggled myself out of that situation, but that is where it started.

I was in the process of applying to top ten business schools: Harvard, Stanford, UCLA, Northwestern, and Penn. I didn’t know why I was doing it. I’m like, “Is this really what you’re gonna do with your life? Maybe I should’ve thought about this more growing up, but this is the path that I’m on, and it seems like the next thing to do is to go back to school.” But this instance sent me reeling.

This is November of ‘97. I’m going through the business school application process. At the same time, my five closest friends that I would’ve talked to about this, all over the course of three, four weeks, all coincidentally left New York City—job assignments, relationships, leaving town, whatever. Perfect storm. Bad happenstance.

I started losing sleep for the first time in my life. I never pulled an all-nighter in school. I never had to. I just had a really good memory and picked things up quickly. School was easy. But now, I couldn’t sleep.

This is why I call my suicide attempt egotistical. The data I was getting didn’t match the story of myself that I told myself.

I went three months where I slept between zero and three hours a night. I wouldn’t sleep at all, and the next day I’d pass out [for] two to three hours. Then, maybe I’d sleep an hour, and then a night with no sleep, and then I’d sleep two or three. I kind of vacillated between none or half an hour or two to three [hours of sleep] for three months. I don’t care who you are, I don’t imagine there are many people who could maintain sanity on that much sleep. I’m not someone who did. I became unreasonable. I lost my sanity.

I was losing sleep. I didn’t have the people who I would talk to normally.

I remember my exact first suicidal thought. It’s right out of a movie, but this was before the movie, and I think the book, even. I certainly haven’t read the book. This experience happened in Canada, in Toronto. I was back and forth Monday to Friday on a plane from New York. In the midst of when I was rolling off of that project—after that guy asked me that question—and starting to lose sleep is when it happened. The thought that I’d be okay if this plane went down. I fell apart quickly.

It was November [of 1997], I think, when that question incident happened, and it was Sunday, March 1, 1998, when I went out for the second time with a rental car [and other equipment].

Working to end your life is miserable.I can say that and smile, saying it to you, because I know you know.

It was a dark, dark time… It was a long day looking around for a place to set the rig up. I set the rig up in one spot, the gas hit me for the first time… and I had pills with me, which I didn’t take. That would’ve been pulling a trigger, and I wasn’t there. I wasn’t to that level of certainty about taking action. I wasn’t compelled to take that action. I’ve told people that me being in the car and breathing the gas in, it was akin to the same thing I did when I sliced through my skin. I was just kind of trying it on, knowing that it didn’t fit. It was almost like I wanted to taste or experience this absurdity, like, “Really? You clearly are not well, and you are deathly afraid of telling anybody about it.”

I eventually did. One of those five people, my closest friend, I literally used the word at the end of a long conversation—after some alcohol up in Boston—I said, “I’ve even gone as far as thinking of killing myself.”

To which he said, a tear coming out of his eye, “Well, then you’re not as smart as I thought you were.”It was actually a loving, beautiful thing, and we both kind of cried, but then nothing happened. There weren’t additional conversations, he didn’t tell anybody, and I went on my way.

Back to the first time the gas hit me: I got out of the car. I got out because I thought, “If I don’t, I’m gonna pass out and die. We don’t want that.” I got out of the car, undid the rig, drove back to near the Holland Tunnel, and stared at the skyline for a half hour. This was Sunday. The Friday before, I had called EAP—the Employee Assistance Program, right? First time ever. I had an appointment—would’ve been my first mental health appointment—on Monday. So here I am now, Monday morning, 12:30 or 1:00 AM, hours from that appointment, right?

I thought, “Okay, you can just suck it up, go home, not sleep, wait til the appropriate time, get out of bed, ‘cause you won’t have slept, call work, tell them you’re not gonna make it in, and finally admit that you’re falling apart and you don’t know what’s going on. Or, I don’t know, maybe go back and try that again.”

I can’t say why I chose the latter, and I really do believe that the same exercise of getting in the car, feeling the gas, ripping out and redoing it… there was a part of me that said, “That’s what I will do for the rest of the night until the sun comes up, and then I’ll make that call.”

I went back into Secaucus, went into the car again, redid the exercise, and the moment never arrived. The moment where I consciously felt the gas hit me, like, “Oh, I’m gonna pass out.” That moment never occurred because I finally did what was so challenging for me to do at that time. I fell asleep.

I fell asleep and woke up. I had a near-death experience as a result of acute carbon monoxide poisoning. I eventually tracked that down. I got my medical records from the Jersey City Medical Center. No one told me. There was no talk about it after I woke up, but I had this memory, an unmistakable thing in my head, and I finally found it: “Pulse and respiration unobtainable en route to hospital.”

Des: What happened after?

Francesco: I was put on Paxil and began seeing a psychiatrist and a psychologist. I saw the psychologist twice a week and I saw the psychiatrist for med checks. This is, my God, 18 years ago now. Mental health care was even in a different state back then, right? The narrative of, “You have a chemical imbalance in your brain. This is the answer in this little bottle… This is your problem, and this is the answer.”

That narrative was much stronger. Sure, there was Mad Pride and all of that, but they’ve come that much further, I think. And I even see it. How many doctors now will talk about alternative treatments and are open to things like meditation, talking about how much nutrition impacts how you are? What a novel idea. You are what you eat.

Backing up, though: my initial recovery, how I lived through it… Again, my good fortune continued. They didn’t know what the hell had happened but, in an unconditional way, I was embraced by my family and my close friends, and kind of given the time and space to get well. And I did.

What did it look like? It looked like I was fortunate. I remember I was excited about this once I realized it and I was convinced to do it. I had been paying into disability insurance.

I said, “No, no. I’m just gonna resign.”

My father said, “You are not gonna resign.”

My boss eventually said the same thing. So I took it. I went on disability so there wasn’t that financial worry. I read a lot. I moved home to Delaware. I went on walks in a really pretty park in Delaware. It was slow.

I’m not dogmatic, really, about any potential treatment. I’m not anti-medication. I have a very different view of it personally, for myself, than I did when I was 27. I will admit, it is my view that the treatment plan that I was put on had worked for me, working through things with my psychologist and whatever—not that anyone really knows what Paxil did to me. It all kind of came together that, within about three to four months’ time, just about as much time as it took me to fall, I was, as people often say, “Feeling like my old self again.”

I actually remember when I felt hope for the future for the first time. I was in bed, and I had had a practical idea about how I can kind of ease back into life. That actually caused an all-nighter, of sorts. It very well may have been the beginnings of iatrogenic mania induced by Paxil, which is a whole other thing.

I really went through an interesting [but] rough—especially for my family, and for me, too—patch of four years. A lot of it was, I think, contending with what had happened. Some of it, certainly, was just living through a suicide attempt, but also, there was the added thing of near-death experience.

These experiences, they can be transformative, and they can have a big impact. For me, they had a big impact on how I experience and relate to fear, or the lack thereof. Simply put, suffice it to say, when you operate without fear, that can be really scary for people who care about you.

My journey is a long one, just given my makeup, and I think my background [as] someone in systems, as an analyst, that’s what I do. I’m a problem solver, so it’s like, “Okay. Examine that problem after the fact.”

I have a picture of the thing I drew in the mental hospital, which shows all these question marks. It’s so funny, because I can’t draw, but it has: therapist, family, friends, positive thinking, realistic expectations—it’s like this little neighborhood, right? And then there’s all these streets and there’s all these intersections and I have question marks in them. And up here, there’s a little cul de sac, and then it says “new career,” ‘cause at the base, I had this dissatisfaction with what I was doing.

Tom Brokaw was my commencement speaker at Notre Dame, and the last line he said, I never forgot it: “It’s easy to make a buck. It’s harder to make a difference. We need your help.”

A lot of my crisis with what I was doing at 26, 27 [years old] was that I was making a buck. I was doing well with that, but I wasn’t making the difference that I believed in. So really, what I have been doing since then? Even though I’ve had tons of opportunities to kind of go towards things that I was more intrinsically motivated about, something more creative, something maybe to do with film, I never really embraced them. A lot of it was a push and pull between I don’t want to say standard of living, but the type of life that you want to have and the resources that that requires as far as what society values.

It’s really been a journey trying to do what I’m doing now. This is the third time that I have left IT and finance to do something in behavioral health. I think I’m gonna make it this time. We’ll see.

That was my immediate live through this. The longer term one, though I won’t get into the details of the rocky period.

Des: I’m gonna make you come back to it.

Francesco: Well, we can. But again, then it’s like how much time do you have?

I wrote a piece like this myself, so I’m gonna try to go to that. It’s not only lessons to learn, but outside of the more conventional model of, “Here is an orange pill bottle with a white top, and this is the answer.” I embrace that answer.

I embrace the writings of Kay Redfield Jamison. Again, I was reading. I’m gathering data. That’s what I do.Robert Whitaker, I am a fan of. In writing, he says, “Schizophrenics in countries with no medicine do better than schizophrenics here. What’s going on?” Thomas Szasz recently passed. He is a renowned psychiatrist. One of his famous books is The Myth of Mental Illness.

Living through this, longer term, is the pin I’m getting back to.

I read this book—it was in the first pile right after, but I wasn’t ready for it yet—it was Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, by [David Burns]. CBT, basically. It’s a handbook, a hand manual for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The nature of my depression, and I think the way I look at life and, again, this analytical nature—this book was written for me. We went together like peas and carrots.

Again, when I first read it, I wasn’t ready to hear it, right? I just read it. But on a subsequent reading, over the years, I saw the sage wisdom in it. It was very easy to recognize cognitive missteps, if you will. Mistakes or choices. Thoughts that match what was in the book. Black and white thinking: “It has to be this way.” To me, this is a vestige of being the son of an exacting perfectionist. There’s a lot of power in it. There’s a lot of power in perfectionism, but it’s a fine line. The way I see all-or-nothing thinking is, there’s this irrepressible fierce commitment for things to be a certain way. That’s a powerful thing, and an empowering thing, to a point.

You go past that point, and the wheels can come off the cart. Catastrophizing. It’s kind of tied with that. It doesn’t go the way that you want, and it’s the end of the world. I did that. And again, this kind of goes back to what I said way back when: “Oh, you didn’t have a lot of setbacks or challenges or adversity or failures. So you don’t know that.”

If given enough time and data, you can make sense of anything. All stories are subject to confabulation, but I had been working on telling this story for too long.

What else from living through this with CBT? [I’m] kind of now moving towards mindfulness, really getting that there are things that happen in this world, and then there are things that you think about. Something happens, and people say something about it. Those two things are never the same thing. Ever. They can’t be. One is an event or a thing that exists in a time/space reality. What we say about it is something else entirely. [It’s an idea].

That was a big get. I came away with what my email address is. My email address is—

Des: Incredulity.

Francesco: Incredulity. The lesson for me is to doubt everything, especially yourself. Doubt authority; question authority—especially yourself. I fell prey to the answers that came out of my head. From my experience, they were almost always right. Again, it’s Bellafenteism. It’s Bellafente Disease. We’re the sons of our father. We’re always right! If we’re wrong, refer to the first thing.

Letting that go and being open to not knowing and being wrong and getting it wrong, that was a key learning for me. That put me onto the path—although I didn’t really get there yet—this notion of mindfulness, of separating an event and an occurrence from what I thought or felt about that event or occurrence. I think that’s a really powerful lesson, the notion of being more deliberative and responding to something, to kind of put a fine line on it. Responding to an event versus blindly reacting to it.

I started off our conversation saying how easy my life was and my appreciation for my good fortune; for advantages, privileges, luck, blessings, gifts, whatever. All of that. If I am anything, I am grateful. I will find a reason to be grateful that I’m walking in the rain. It’s not every day you can walk in the rain!

Whatever it is, I’m always careful… That said, there is something to being present to your good fortune, no matter how small it is. Obviously there’s a trust in here with you. [You might think], “Oh my God, he’s just telling people they need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps.”

No. I’m not saying that. But when I look back at how I used to think from 27 and earlier, and how I came to think in the years after that and now, I almost don’t recognize the thought patterns. Gratitude saves me and sustains me over and over again. That’s a big one. Gratitude.

Then there are basics. Coming out of school, my attention to diet and exercise, I’ve grown so much in that regard. I dated a vegan for a while. The relationship lasted three months. I was vegan for six months and vegetarian for four years. The person, she just had this amazing discipline about an exercise regime. I took that from her. I borrowed it. Made it my own. I became a distance runner and experienced a runner’s high for the first time. I lived in Westfield at the time, and it was on the Schuylkill River loop. Eight miles. It was the first time I ran probably more than four miles. I ran eight. I thought, “Oh my God. I’m high, and I didn’t smoke anything!”

I had a transformation around really getting that I am what I eat, what I consume. [There are] unmistakable benefits. For me, I know it’s different from person to person, but from the ability to concentrate, focus, and sleep as a result of having run that day. Or, taken on the broad scale, keeping up my regimen just keeps me balanced, keeps me in the realm that I want to be in.

I guess, back to the new career cul de sac… Who said, “Everything you want is on the other side of fear?” Striving to live purposefully versus just sustaining yourself. To me, this is the definition of growth.

I’m 27 and I’m doing very well in my job as a business systems analyst working in IT and finance, but I’m not connected to a larger purpose. At that point, my purpose is to just do as well as I can like I would be at school. Just get the best grades you can. Try your hardest. It was empty. I wasn’t hearing Tom Brokaw’s advice: “It’s easy to make a buck. It’s harder to make a difference. We need your help.” I was just making a buck.

Fast forward. Go back. I continually go back to IT ‘cause it’s what I know best. It’s what I can make the most money at. There were not intrinsic rewards in me. Finance serves a purpose, whatever, allocation of capital to solving problems in society… blah blah blah. I’m not really buying that.

That’s not my purpose, but I do have a purpose. This is one that I’ve wrestled with for so long. What am I going to do from an activism standpoint? Am I gonna do anything? I wrestled with that off and on for years. I’d think, “Are you going to do something about this, or are you not?”

It’s telling to me that X years later, I can be doing work in the same field, essentially the same work, and because of my purposeful living outsideof work hours, I have no problem at all. But I can do that. I can do that for a time. It is a means to an end. To me, that’s the growth. [You might think], “But wait a minute. You’re 37. You were 26, and you were doing X and you were miserable. You’re 36, you’re doing the same thing, but you’re not miserable. What’s the difference?”

I had a purpose, and it is the cause. I’ve done so many little things. A lot of them were private. Abraham Biggs. It was Justin.tv, before Periscope or whatever. This would’ve been about nine years ago. He died by suicide online, live.

You know what Google Alerts are?

Des: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Francesco: I created like a suicide safety net. I put like 100—too many at first—suicidal phrases and quotes. What’s Google gonna do? It’s gonna find them and send them to you every day, every week, whatever you ask for.

Des: I have them, too.

Francesco: Right. I’m sure you do it to find attempt survivors. But I would do that and I would find people and then I would armchair CBT them. I went through the whole, “Maybe I want to become a psychologist.” That’s not what I want to do.

Des: What was your experience with the other patients in the hospital? The doctors? Did you get anything meaningful out of it, good or bad?

Francesco: I loved the patients. I think of people in mental hospitals as my people. I’ve been in a mental hospital twice. The first time, the overwhelming predominant state for me was shame. As I already said, I was not oblivious to the depth and breadth of human suffering that goes on for people here in America or anywhere else in the world. But it’s one thing to know that story you see in the newspaper, or on the Internet, is happening to people. It’s one thing to know that and for those stories not to be happening to you or people you know and love. Then it’s another thing for someone, that horrible, painful, traumatic thing—being in a war, killing people, seeing people die, physical, sexual assault, abuse, emotional, psychic abuse, manipulation—just the horrible things that people do to people. It’s one thing to know them as a construct, as an unattached made-up thing in the abstract, and it is another to see and hear someone tell these stories.

I did not want to go into that place. I remember sitting outside. My family was there. As I’ve already told you, I just needed to sleep, and I was convinced that I would’ve had a better chance of sleeping at home at my parents’ house than I would at Rockford Center in Delaware. But as I tend to be, I am so grateful that I had the experience that I had there.

At the same time, I completely fit. I needed to be there, and I felt out of place. There were many people suffering from life events that my experience did not match, as I’ve already told you. It made my experience a very quiet one.

I really liked my roommate, and I had friendly conversations with my fellow patients. But I was embarrassed and ashamed to talk about my problem as I saw it. At the time, I would’ve said, “I had some trouble at work. I wasn’t able to sleep, and I really didn’t know where I was going with things here.” The way I put it then was, “I came as close to accidentally killing myself as someone can.”

It really wasn’t accidental. My suicide attempt, my suicidal behavior, fit my suicidal intentionality to a tee. I wanted to create the chance to slip away, to almost die by an accident, semi-intentionally. That’s almost exactly what happened. It gave me, what I see, as the most valuable experience of my life, which is the NDE, which I’ll get to again.

A little more on the hospital, though: it was clear to me from the first visit, and especially the second one—and I’m gonna talk about staff versus the doctor—that these people are the salt of the earth. You don’t work at a mental hospital for the money. Certainly not staff. These are good people. Not that I got close with any in particular, but this is a lot to deal with. There’s a lot of jobs that one can do. What brings someone here? It’s gonna be something personal in some way, shape, or form. It’s not gonna be, “Oh, that’s a job that I’ll take.” These people have a special place in my heart.

My doctor… I was underwhelmed. I was there for five days. I probably saw him for a total of maybe ten minutes.I have really good insurance. Again, very fortunate. But I’m reviewing it after the fact. You get the doctor’s bill separate [from the hospital bill]. Individual psychotherapy, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Five times.

I was like, “Wait a minute. I was there five days. We had one sit-down, and then I talked to him a second time, standing up at the main desk. And then I had one two-minute goodbye.”I saw the man literally three times.

I remember being on the phone, first with my insurance. They said, “Well, this is what we got.”

I eventually got an assistant at his office saying, “That’s just how we charge it. There is a charge every single day that you are in the hospital.”

I said, “Okay, but it’s labeled Individual Psychotherapy. How can the man deliver psychotherapy if he literally didn’t speak to me or see me? We talked by phone, and he didn’t see me. Was he telepathically psychotherapizing me?”

My insurance company didn’t care. This is institutional corruption.

Des: I’m curious about the near-death experience.

Francesco: My near-death experience was the most painful, the most terrifying, and the most transformative experience of my life. [It wasn’t] the Hollywood version, the version that you hear: bright light, end of a long tunnel. Life review. Maybe some guide. Jesus, or a relative. I don’t know. Obi-Wan Kenobi. Who knows, right?

Des: Patrick Swayze.

Francesco: Patrick Swayze to shepherd souls along their journey over the river. What’s the river? Charon?

Des: Styx.

Francesco: Styx. Mr. Charon. I was familiar with that, but I woke up a few days after this experience. My experience was nothing like that. It sent me on a years-long search for descriptions like mine. It was years, and I finally found it. It was a book called Dying to Live by Dr. Susan Blackmore. She’s a British psychologist, I believe. And at the very end of the book, she writes about this guy who talks about this infinite black void that he was in. This is the neighborhood of near-death experiences that I was in. Boiling it down—have you ever had a lucid dream? You know what that is?

Des: Yeah. Yeah. I would say I have.

Francesco: My definition of a lucid dream, as I understand—

Des: You have control.

Francesco: Right. It’s like you rise up into the layers of consciousness. You’re not conscious, but you are aware that you are dreaming, and you can take control of the dream. I’ve only had those a couple of times, and I wish I could have them more often. I know there’s ways you can work on that, but I haven’t spent time on them.

This memory was akin. The state of consciousness that it’s closest to that I have as a reference point is lucid dreaming. But this wasn’t a dream. It’s always been there, that’s the other thing. It’s a memory. But unlike every other memory of my life, this one doesn’t go backwards. It just stays. The farthest it is, is yesterday. It doesn’t recede. I always have access to it.

Which, again, is leading up to the benefit thing. This took time to get it, but I had the benefit of years of thinking about it.

I faced in the moment, consciously, the greatest vulnerability that we all have. Death is an enduring mystery. It’s the greatest unknown, I think. It’s one of them, anyway. I woke up into a lucid dreamlike state. I had what I’ve come to refer to as the only problem I’ve ever had in my life: I was not breathing. You’ve gotta breathe. I wasn’t breathing.

I didn’t know why there was just blackness. I couldn’t see anything except the blackness. The only thing I could hear was the voice in my head. The voice I’m speaking to you in. I don’t think it lasted that long. I wasn’t breathing, and I didn’t know why. There was no recollection of the car. There was no suicide mentality in this memory. There was just not breathing.

Very soon after not breathing, there was pain. All-encompassing pain. So there’s all-encompassing blackness, there’s all-encompassing pain, and then, very quickly, there is, “Oh my gosh! This is real! I am not breathing, and I have to breathe!” So now you’ve got fear. Pain kept increasing. Fear turned into terror. There was nothing that I could do. Your mind is like, “You’re choking. Unchoke yourself. I can’t move my arm. Why can’t I move my arms?”

I’m eventually screaming, wailing inside my head. You have no sound. No change in the visual. I’m just trying to breathe. I’m trying to be. The pain’s going up. I think it’s the most vulnerable that someone can be, and I think, it’s why I said it’s transformative. But it’s also the most empowering. I confronted head-on, “There is going to be a point where you will not be able to take a breath.”

It’s a scary thing. I just went there when I gave up. In my mind, there was really no choice there, either. There is no, “Uh, maybe I won’t try to breathe.” You can’t not try to breathe. Does that make sense?

Des: Yep.

Francesco: You can’t not try to breathe. You can try to. Sure, people can blow their heads off. People can kill themselves. But the instinct to breathe is irrepressible. And I remember when I couldn’t try anymore. There was no choice in that, either.

For me, the heart of my near-death experience is vulnerability.

Des: I wanna know about the benefit and then, is suicide still an option for you?

Francesco: Benefits are clear. Again, who I am—what I am—forget who. Analytical, aspiring to be a figure-outy type person, right? I have a good memory. I can slap words together. I have deconstructed my lead-up to suicidal behavior that almost cost me my life. It almost cost me my life. That has a benefit for me. In taking apart the missteps I took, I’m empowered and informed, to a degree, that I was not prior to having that experience. There’s value in the lessons learned. A lot of it was just mapping on Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy to my life. This stuff is straightforward. So there’s the personal benefit of lessons learned. This is a protective factor, right? It safeguards me against suicide.

I think I wanna jump to your question.Is suicide an option? If you were to—your wife, a loved one, a family member—if you were to knowingly sacrifice yourself to save their life, is that suicide? You know what I mean? Is it?

Des: Depends on who you are.

Francesco: What is suicide? Right. My email address wants to keep me from saying I don’t want to make dogmatic, absolute, certain claims about anything. You saw The Matrix, right? We can’t prove that that’s not what’s going on! You get that. I’m sure you do.

Des: That’s kind of why the question is designed the way it is.

Francesco: Yeah. And it’s almost like I want to take a cop-out on it. It exists as an option. I don’t wanna say I’m unable, but I struggle. It takes quite a bit of energy for me to construct a scenario where I think I would end up even entertaining the thought.

I have never been suicidal since my suicidal behavior, which is not to say in the aftermath of it, and in that four-year window later, that I didn’t have suicidal thoughts. I did. But I took steps. ‘Cause it’s just a voice. It’s just an occurrence. A thought pops into consciousness, right? I don’t think we choose our thoughts. I think they just arise for who knows why, right? The cosmos.

I took steps. I was compelled to take steps to not hear those voices. And I have been successful. I am writing a story about that while fully admitting that it’s bullshit.

Francesco: I don’t know about you, but I see my attempt in other suicides, right? Again, I’m making it up, but I forget her name—the nineteen year old.

Des: Madison Holleran.

Francesco: I think I know what happened there. I think that was like mine, just much younger. For me, that happened when I was 26/27.

Des: Yeah. You feel it. You know it.

Francesco: Right. I don’t know. Actually, I imagine—I hope—that loved ones will be like, “I think my loved one was you.”

I, too, know that suicidality does not discriminate. There are types, and there are things that people do in their head.

I say that my suicide attempt resulted from the story of my life going a way that not only didn’t make sense, but I could not accept it. The self-destructiveness of suicide is a failure of creativity. It’s the turning of creativity to the dark side. I wrote something a long time ago. I said genius was a prerequisite for suicide attempt. If you look up genius, you can find some definition to say “extreme creativity.” I have no problem saying this to someone who has come this close to extinguishing the light of life within me. There is no greater force or instinct to overcome than that, than the desire to breathe. Even if you have all the life events in the world, actual tangible things, not just some neuromal storm that makes you feel like shit, right?

This is where you get the whole courage thing—how creative one has to be to make sense of suicide. I think it takes huge amounts of creativity. Does that make any sense? Because when you are in the process—when I was in the process of almost killing myself, I could make sense of it. There was a sense now. What sense was that? It was the sense of someone who had slept zero to three hours for about 90 days. I will fully stipulate that there is delusion in that.

People talk about depression with psychosis. That’s kind of where I go to with the anthropomorphization of depression, of mental illness. It’s not being critical of people’s writing, but it’s just concern. When I hear the way people are thinking about the monster in their head, I think, “Err, I know that wouldn’t empower me.” I question sometimes if it’s empowering people.

The brain is the most complex, and therefore, necessarily the least understood object in the known universe.

Thanks to Taryn Balchunas for providing the transcription to Francesco’s interview, and to Liza Larregui for editing.