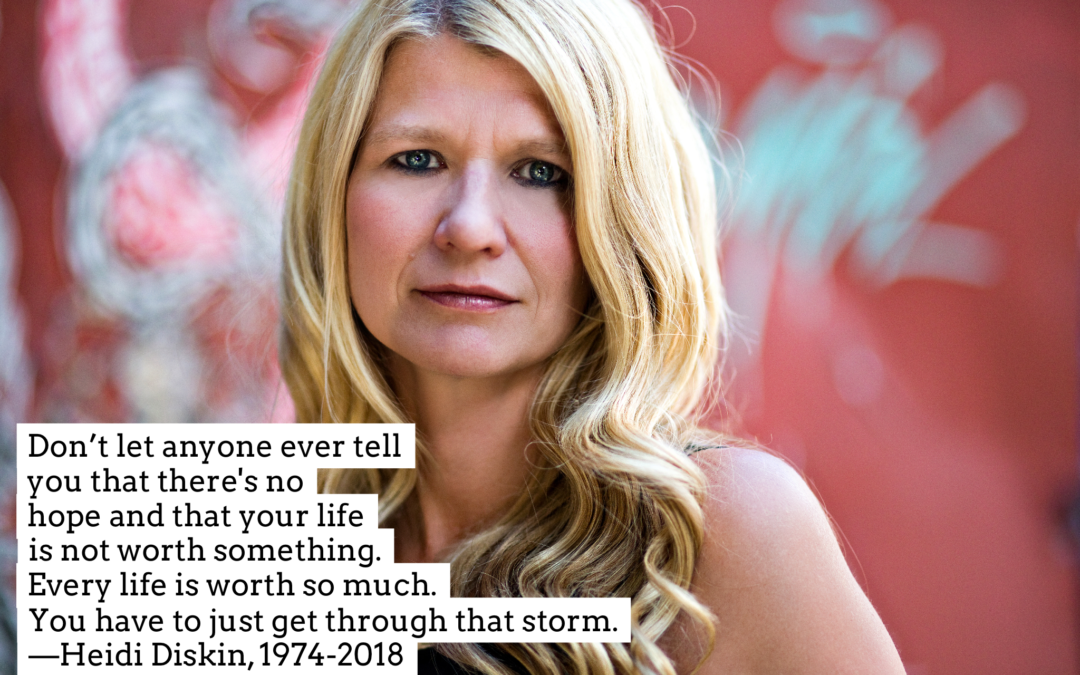

Heidi Diskin

In Loving Memory of Heidi Diskin

Heidi Diskin was a landscape designer and mental health awareness educator from Wayne, Pennsylvania. She was 42 years old when I interviewed her in Philadelphia, PA, on August 4, 2016.

Heidi died by suicide on September 7, 2018. Heidi’s story will remain published here because she was a member of the Live Through This family. We sat across from one another in a cafe, and she shared her story of survival with me. We bantered back and forth about our work. It was wonderful to spend time with someone so passionate about the same things I’m passionate about. Even though she’s gone today, her story remains as an important reminder that, as suicide attempt survivors, we are each still at risk for death by suicide.

Please read this story with care. If you’re hurting, afraid, or need someone to talk to, please reach out—to anyone, anywhere. Someone will reach back. Please stay. You are so deeply valued, so incomprehensibly loved—even when you can’t feel it—and you are worth your life.

I guess I started having depressive episodes in the beginning of college. I don’t think I knew at the time what that even was. I had no idea why I was going in my room and not speaking to people. I was too young to know what was happening to me. That was probably at the age of nineteen.

I was away from home. I [bounced around a lot] in college, so this was a place I was unfamiliar with. I transferred to a school out of Penn State called Salisbury State University. I was kind of out of my element and away from everyone. Now, when I look back, that’s when it started. I guess, if you asked one of my roommates then, they probably thought I was pretty strange. I didn’t come out of my room, didn’t speak to anyone.

That’s kind of the first time remembering it. Over the course of time, it would come and go. I guess it was more depression than it was any kind of bipolar, which is what I’m diagnosed with now. It would come and go. I started to recognize it when episodes came more full on.

My home life growing up wasn’t “perfect,” so maybe some of those things contributed to how I felt. As things continued through my twenties, I would go in and out of depressive episodes and not see anyone for it—just kind of try to push through it. There were probably even minor attempts that were kind of there, things I didn’t even realize until now—veering off the road, or things I just don’t talk about.

Then, I met my husband—he was my boyfriend at the time. I was twenty-nine years old and we [became “of age”]. We get married and still things are kind of in and out, and you just kind of fake it and fake it. Not trying to cover it up, but you just want to be like everyone else, I guess.

After we got married, I kind fell into my lowest low. Pretty catatonic almost. My husband noticed things, but not enough. I was still trying to cover it, but I was Googling ways to kill myself night after night. That kind of stuff. They didn’t feel like my choices, I know that. I think it was my disease’s choices to be doing that.

I guess the biggest trigger, now that I look back, was something that happened at my wedding with my dad.

My dad was like my saint. He held up the boat, and my mom was the one who struggled. She was sexually abused by her dad. She was always mean to us growing up. She was just this non-stable person. [My dad] was everything to me and my sisters.

I can look back now and see what happened as a potential trigger. My wedding did not go so well, out of nowhere, based on my dad. I didn’t invite my mom to my wedding for fear of her episodes or her freaking out, or many, many other things. The wedding was in Puerto Rico, and my dad was a little upset about it. He was upset about it because, he said, “You should at least invite her. She’s your mom.” That’s all I knew going into it.

I guess, as he was walking down the aisle, he was shaking. You could tell that it wasn’t a joyous shake. It was an upset shake. You look back at the video now and you see there was tremoring. He was obviously upset.

We go into the cocktail hour and I get screamed at by him. [He] was emotional and upset, and that was actually pretty awful. I was in a bathroom stall bawling my head off. I thought I was preventing this by not having my mom there. I didn’t know at that time where that came from. Because he was everything that we needed him to be, that did me in. He gave me a reason then. We didn’t speak for months. It all makes sense now—how he felt. It was pretty bad.

People know about my attempt with the pills, but there are things I just don’t want to say, even to my husband. I couldn’t say, “Um, you know, I was down under the bridge in Philly…” Crazy stuff—the ways that my brain was telling me to take my life with charcoals in my car—shit your brain decides to tell you to do. All the [thoughts] that go behind it. How do you explain it to anyone? How do you make it seem like it’s not… for me, anyway, it’s not me. It was this stupid thing in my brain telling me to do this. It’s the loneliest feeling ever, obviously.

Then I was in the hospital. That’s what finally got me a diagnosis after, like, thirteen years of being undiagnosed and going through all those things. I’ve had the same girlfriends since then, but they probably shied away at times because they thought, “There’s the crazy girl.” Not that I’m saying they’re saying that, but at least now I feel like there’s a reason for it. Finally, I was able to get on medication that saved my life. If I had kept going in that direction…

Nobody in my family picked up on it or wanted to pay attention to it. It’s not their responsibility in any shape, but that’s why I want to fight for this. My husband didn’t know what to do. It was a lot of years of up and down—mania, depression, mania, depression.

I was completely in recovery that year after. Obviously, I wasn’t immune. There were still bits and pieces. Even after I had my first child, I still had a bit of depression. It’s a rocky road, like we all have.

It’s just one of the loneliest times I think a person can experience. It’s hard to describe to people that I think it’s not a choice. It’s not something I feel you’re in control of. So many people say [they do it] to hide their pain or to get rid of their pain, but I wasn’t consciously trying to get rid of any of that. My brain was doing that.

I wasn’t going to kill myself to get rid of the pain, because I wasn’t consciously making a decision to kill myself. I really think I was trapped in there, and that little disease was in the driver’s seat making that decision. I was not in control of my thoughts at that time. I don’t know if that’s how it is for everybody, but I wasn’t in control of those thoughts.

It always pisses me off when I hear people say that I’m making a choice. Maybe it is for some, but who would choose that? Who would really make that choice? Really tough, especially when you realize what just happened, and you’re in the hospital like, “How did this happen? Don’t tell people,” because then you have to worry about what people are going to think of you. It’s like, “It wasn’t my choice. I didn’t choose to do this.”

I hate to think of the pain that people go through because of being untreated. [I was] undiagnosed for so long, and that’s happening to other people. I don’t want to see that go on, because it’s unnecessary.

I think there was a point where my dad knew. He knew I was there. He had seen it with my mom, and my mom had several attempts. [I was] seven years old, 3 A.M., praying in a circle with my grandma and aunts while she was in the bathroom. It’s like he knew it, but was afraid to say anything or go further. He’s like, “Oh, Heidi. You need help.”

I’m like, “Yeah, I know I need help. It’s not anyone’s duty to get me the help, but since I am not thinking straight, I need someone to help me get the help.” I needed him, even though I was thirty-two, to take my hand and get me there. Again, it’s not his place. I have a girlfriend who attempted four times, and she’s like, “No one can do it for you, you have to hit rock bottom.” That’s true, but you can be as supportive as possible up until that point.

It was a crazy, tumultuous little situation, and wasn’t really how I wanted to start my marriage. Sure, it’s been hell for my husband. He doesn’t talk much about it. He’s always the funny guy, not very emotional, but I’m sure it’s been really rough on him. It’s been eight years now, but last year is the first time I decided to even bring it to light.

You know, [I] can’t hear about these young teenagers—whoever, it doesn’t matter who it is—and not stand up and do something. It’s bullshit to have it be this quiet, hidden thing… especially where I live. Those parents, they’re just like, “Oh, not my kid. Not my kid! My kid is a private school, trust fund kid.”

It’s like, “You guys, what are you talking about? They’re not choosing it. You can’t do that.” That kid who just jumped off the Ben Franklin Bridge two weeks ago [was at] the same private school—Shipley, a $35,000 [a year] school—as the thirteen year old kid who was missing last year.

That’s what prompted me to start thinking about talking about it. I didn’t know there were organizations out there talking. Then an older, wiser woman brought it up and talked about this group called Minding Your Mind around here.

But those two kids are both from Shipley, and that school’s still not going to do anything. As of last week [they said], “Oh, here’s postvention. Here’s grief counseling.” That’s not going to help. Parents are such a terrible group for me. You guys have to know what to look for. You have to know how to spot it. I think that word “mental” has to go away. It needs to be “brain disorders” or “brain illness.” The word “mental” has too many negative connotations to it. We need to associate it with more good.

But…that’s my great story!

Des: Tell me more about the aftermath of your attempt and the hospitalization. More about what people around you [did], how they reacted, and how they were helped—or not.

Heidi: No one was really helping or wanting to talk about it. It was like, “Leave the hospital and get to a doctor.” I, myself, kind of knew, then. Nobody was really running to tell anyone what happened or saying, “This is how I’m going to help.” Nothing changed with my sisters. In fact, they completely ignored it. There was no, “Okay, we know this is it now. Let’s see what we can do to help you through.”I don’t feel like anything changed. Fine, I had the tools. I know now I can go to the doctor and start treatment; so, that’s what happened—seeing psychiatrists, getting on meds, and starting therapy.

I missed a point. There’s a lot of memory loss stuff for me. I wasdoing talk therapy a little bit prior [to the attempt] because my husband kept encouraging me. Once my therapist heard about the attempt, she was so upset. We were at University of Pennsylvania. She was a professor there. She got me outside. She was visibly upset because she felt like she didn’t do her job. I hadn’t been seeing her very long.

There’s nothing that changed with the family. There was quiet supportiveness from a couple of them. My husband’s dad and step-mom came to the hospital so, in some ways, that was some support. But there was no talk about it. Again, we’re not gonna be chit-chatting, like, “Oh, yay, this just happened!” At the same time, there was no, “It’s okay. We can talk about this,” or, “You don’t have to talk about this.” There wasn’t any of that.

It’s still just quiet. It’s a weird thing to talk about. Even my dad—always a quiet person, anyway—was obviously concerned, but it was just difficult to talk about.

It’s weird because we’ve had a couple houses in Philly. You leave and you can go on with your life, but I think about those houses and I have these badmemories attached to them. It sucks. It’s like, you want it just to be all good—you got married, you had your kids—and it’s like, why?

Therapy and the medications obviously helped tremendously. It helps keep me stable, which I’m thankful for. But it’s a tough time!

Des: Now that you’ve decided to do advocacy work, have you talked to your family about it? Do you feel like you’ve taught them anything?

Heidi: I do, but it’s still not a full conversation. There’s still a lot of hesitation, even with my husband. It’s understood, and I talk about it a lot, as in, “It’s a medical condition.” For me, this is what I say: I feel like my suicide attempt came from the bipolar. Not that I care about what others think, but if we’re going to change some stuff…

My husband and I were just talking about doing a fundraiser. I might be applying for a fiscal sponsorship and do a small non-profit. I want to get the awareness out. I want all of these people who have a loved one or kids to know how to spot the signs.

I don’t know how many people are still going to not go near it because of the stigma around it. I feel like, is my husband even one hundred percent full-on because of him caring what other people think? Because I don’t care what other people think. I don’t want people to go through this. It is god awful.

It’s hard to change people’s minds when it comes to this. It sucks. Obviously, it’s not the most favored thing to talk about. It’s upsetting. It’s upsetting to a family member, I’m sure. I didn’t want to do that. My brain took me there.

It’s just kind of what I say because, in the town where we are, two parents lost their eighteen year old three years ago. The mom is starting to do these clubs on college campuses for a safe place to talk. The first day I met them was the first time I talked to someone who lost their child to suicide. I was just dying to tell them, “He didn’t want to leave you.” I don’t know them, I don’t know why I thought that it was okay for me to do that, but it’s because I just wanted to tell them, “It’s not your fault.” There’s a lot we can do, we just have to get people to listen.

Des: Yeah, that’s an uphill battle.

You said it’s been eight years? What have those eight years been like?

Heidi: Better! Better, because it’s been more stable. There have been a couple dips. I was on Lamictal for a while, and I don’t know if it started to wear off, but 2014 was a bad year. That’s my third house with memories. It’s hard because, when you hit low, even your bedroom [gets] associated, like, “This is where [it happened].”

It’s been fairly good, but there’s been a couple of those dips where it’s mostly depression with some highs from the mania. It’s been much better from previous times though, so I definitely think the medication helps to stabilize it.

Des: If you get the right stuff, which is hard.

Heidi: I think my boys help. I mean, I hope that, even if I didn’t have my boys, I would still [be okay]. I’m not saying, “Oh, it wouldn’t help to have my husband.” It’s just that those are two little bodies that are reliant on me. But again, when I say that, it makes it sound like I’m making a conscious choice to be okay or not be okay. For me, I don’t think that’s how it works. I think that, if something switches in my brain, I’m not consciously deciding to go downward. I guess I shouldn’t have said that, because that makes it seem like I’m choosing when things go south.

Des: Well, they’re a protective factor, right?

Heidi: Yeah, for sure.

Things are definitely better, but there have been some bumps in the road. But, my brain’s different! I’m going to get a CT scan of my brain and compare it to my husband to see! Nah, I’m just joking.

Des: Do you feel like you’ve had any benefits come from your attempt?

Heidi: Wow, that’s an interesting question. Well, I got treatment and got a diagnosis. I mean, I wouldn’t want it to go that way, but you know how serious it is when you look back.

I was praying it didn’t hit [a specific family member], but it hit her last winter. Her daughter is a teenager—seventeen. She saw her mom, and she’s like, “I think something’s wrong.” Because of [my experience], I was able to save my family member that day in some ways. Other people would not have noticed, or they just wouldn’t take anything seriously. I mean, she wasn’t saying anything. It wasn’t like anybody necessarily knew she was going to attempt. I just knew it, so I drove there.

She disappeared and I had to find her that night. We had to get the police. We tracked her to a hotel.

I stayed to see,and my girlfriend was like, “What are you going to do, just stay there?” She’s the girlfriend who has depression and has made attempts, so she was being supportive, but then she was also like, “What are you going to do, stay there all night?”

I’m like, “Yeah, I’m going to stay here all night. She’s my family, and she’s not going to die tonight.” I think having that experience helped me not just shrug it off and be like, “Ah, she’s just saying things.”

That attempt shows you how precious life is. I don’t want to see anyone else go through that. If you gave me the chance (if I didn’t have young kids), I would be already doing a crisis line. Not that I want to put myself through that, but at the same time, I just want to beg and tell that person, “You will be okay. You will recover. You can’t let this take over. That’s not a bunch of bullshit.”

Des: You’ve got special challenges, being a parent to these tiny humans and knowing what you have to deal with. How do you explain it to them when you get depressed ? How do you maybe one day explain to them that you attempted suicide? What does that look like?

Heidi: That looks like far into the future. The depression part, that’s fine. When they get a little older, that I [can do].

They’ve even been asking me, “Mommy, what do you do?”

I say, “I help people when they’re feeling sad.”

My first son will probably, in a few years, be ready to have a little more definition of it. The suicide thing—man, that has to come later. That one’s a tough one. I mean, just the age.

Des: I’m always interested in how parents are handling it or are going to handle it—if you can even plan how you’re going to handle it. I don’t know that you can.

Heidi: What was weird was when I was in the hospital with my family member. Mind you, her daughter’s seventeen and her son was fifteen. Their grandmother—who is biological, but not really in the family—unfortunately had lost her husband to suicide. She’s like, “Oh, you have to tell the kids right away, right?”

I’m standing in the hospital like, “No, I don’t need to tell the kids right away. They just need to know that she’s okay.”

She was sensationalizing it. No, I don’t need to tell them right this second. It has to take time. They’re still kids. We weren’t even out of the hospital.

But, yeah, being honest, for sure. I’m all about that.

It’s hard, but the way I explain it now, it really felt like my brain was hijacked. That was my disease. I don’t want to come around saying I made this choice to do this to myself, because I don’t think it was. Maybe my hands were doing that action, but those thoughts weren’t mine.

To understand the whole gamut of it would be a big discussion, but it’s hard, like, “Let me tell you a story about your mommy!”

It’s all I can eat, sleep, drink, and breathe. Last year, it was all I could think about. I just want things to get better and people to not be closed-minded about it, because that’s what it’s been for so long.

Des: Is suicide still an option for you?

Heidi: Hm, I don’t know. Because I don’t think it ever was an option. I don’t! It was my disease’s option. That was not something that I, Heidi, was deciding. I was trapped in there. If it became something that came up again, it would be me out of control and Mr. Bipolar making his choice.

Des: What does having a diagnosis mean to you?

Heidi: I think, in the beginning, it meant a label that my mom had. I never wanted to be like my mom. That label, now it has a different meaning. Now it’s what I live with, what I have to fight, and what I won’t let overcome me. I’m not going to let it take my life. I fought way too hard to get through it all on my own, really on my own. I mean, there were people there, but…

Having that diagnosis is saying, “You’re not going to take me down.” It can’t take me down because it made my life shitty enough. It really did. I always think of all these girls who had perfect mothers and white picket fence lives. Sometimes I get bitter that way. I shouldn’t, but it’s like, why didn’t I have some of that? That diagnosis sucks, but it’s not taking me down.

Des: How do you cope on the bad days? What do you do?

Heidi: I have to slow it down. I always have to be productive. That’s the only way that I feel okay. I only recently allowed myself to just take a day off and not push myself, because that’s when I go on overload. I just do whatever. Hot baths and me time.

It’s almost kind of like what you say: you know what you need, where you need that extra love, or where you need that space. Support time is huge for me. Feeling alone or abandoned makes things double worse for me. I think, because I felt abandoned with my mom, I need to have that support around me. Friends, my husband—I just need to have support when I go to my little girl abandoned state, I guess.

Des: What could we do better in suicide prevention?

Heidi: I think we’re being honest, but I think we have to be even more honest. We have to make people feel comfortable in talking about it. Maybe get them to talk more about what their thoughts are. Help to spell out some things that we need.

I even did that yesterday. We were asking for auction items, and [this woman] was like, “Yes, I get medication and therapy and I understand this depression thing, but I think it’s about discipline.”

I was like “Oh, man. I’m standing here representing a foundation and I’m about to just ‘go Heidi.’” and I’m like, “It’s not really discipline. That’s like trying to discipline your cancer cell.”

Yeah! Discipline! I can just tell myself to not to feel depressed today! Okay, yeah, I’ll do that right now.

Des: Get right on that!

Heidi: Just be honest and hear what others have to say, so we can maybe dispel anything or educate you more, so we can have an open back and forth dialogue. Everybody is so egotistical, they all know how to say their part. Let’s give them part of the voice and see what they have to say, see what might be right and what might be wrong. Get people talking.

I think we’re doing it, but I think we’ve got a lot more people to hit. I mean, we might hit them for a moment in time and have a one shot assembly, but that doesn’t do shit. Why are we going into schools, having one assembly, and then never doing it again? What’s the point? This isn’t a rash of drunk driving. If there’s going to be depression among kids, it’s not just going to go away, so let’s have it in your health classes. Let’s have regular things going on.

I sat on a panel in April, up in East Stroudsburg. Two sixth graders—back to back suicides. It was my first time ever sitting on a panel—you’ve got the local college professor, the psychologists, and you’ve got me. All this professor’s talking about is statistics, and same with the psychologists. I’m like, “That’s not going to help these parents.”

The parents are out there screaming for help. They’re even saying it, like, “Well, that didn’t really say how I can spot something in my child.” We can’t have these little gatherings where we’re talking about statistics, because that’s not going to help anyone. Let’s talk about [being] withdrawn, isolated—the signs. Let’s talk about then, what you do—step two.

It’s like, [we need] real help, not statistics. Those are not going to help those parents. That’s not what is really concrete that’s going to help us. Let’s not just talk about education, let’s actually give it to people.

Des: Yeah, it’s hard.

Heidi: I mean, if you were sitting with a group of parents and they said, “Oh my god, my son’s so depressed, or something’s going on with him.” Would you say to look for things like what happened to you?

Des: The first thing I would say would not be a statistic. That’s just supplemental information.

I think relatability is the most powerful thing that we have. I think the scientists forget that they need to make their work relatable. The statistics need to have some sort of representation that is relatable. With the STAY shirts, I was like, “Let me sell one hundred and thirteen of these—maybe put one hundred and thirteen selfies on the site, so you can visualize how many people might have died in one day.”

A middle man is what they need. They need somebody who can take the information and convert it into something that’s going to interest the rest of the people, engage them, and make them want to move and do something. They don’t know how to do it.

It’s useful to a point. It’s useful for us to know it, but if it’s stuck in a journal somewhere, and if it’s not converted into real-people talk, why bother?

Heidi: Even that professor, I could have jumped over the table. I mean these parents were clamoring. They were really upset. Several suicides, over the course of a couple years.

Then he’s sitting saying, “Well, if I have that young boy coming in telling me he wants to kill himself, I’m telling him what he’s doing to his family.”

I’m like, “What he’sdoing? You didn’t just say that in this room, did you? Like, what are you doing? He’s not making that choice to hurt people.”

Des: A huge part of the problem with the field is that it’s not consistent. They don’t agree with one another on what should be done half the time, and that’s not even touching how they deal with people with lived experience. It’s like, if a psychologist is willing to shame somebody, we have to teach them before we can teach everyone else.

Heidi: I know. You’re absolutely right. Have you tried to deal with the high schools at all?

Des: I have not been in the high schools.

Heidi: That was middle school, but even still. I was like, “Alright, let’s connect back in two weeks.” I didn’t want to go there and then they never hear from me again.

I was like, “Can I just give you a document looking for signs that you can give every parent?” Because they asked for something. They didn’t come out of there with anything. But I said, “Can I do this?” No response back.

Same with my niece and nephew at their high school. There were two [suicides] just before the school year ended. I went with an AFSP folder. Nothing came back. I’m like, “What are you so scared of?”

Des: Something that has already happened! Like, “Can we avoid this?”

Heidi: Exactly. I don’t know why they have to be so scared about it. Zero prevention or proactivity. It’s just like, “We’ll have some grief counseling and then we’re done.” That’s it.

Des: What would you want to say to somebody reading your story?

Heidi: Reach out and take any hand that’s there. If there’s not a hand there, go grab one and say, “I need your help.” Be able to say those four words, “I need your help,” if no one’s coming for you. There is hope and you just have to get that treatment. Just know that you can make it through. Be able to say, “I need your help.” Don’t think that you can do it on your own, or that there’s no hope. You have a whole life ahead of you. Know that, whatever it is, impulse or disease, it can take you down. It needs treatment just like any other disease. Don’t let it ruin your life.

Des: You said something very similar to a quote I posted from an interview I did recently, which was something like, “If you need help and no one’s listening, be loud.“

Someone shared the post and called Live Through This “positivity porn.” I wrote them a message and I was like, “I think that you’re not really understanding what this is about and where I’m coming from. I’m about honesty, and not positivity, necessarily. But we are all allowed to have our positive viewpoints, and you said something hurtful about a person, not an organization. Somebody said those words, believed them, and wanted to share them,” and, kind of, fuck you for that.

Their response was essentially, “Stop telling people there is hope, because there is no hope. Telling them that there is hope is cruel.”

What would you want to say to somebody who says it’s absolutely hopeless?

Heidi: It is not! It is a fucking thing in your brain that is tripping you right now, just momentarily. It is not gonna win! Don’t anyone ever let you tell you that there’s no hope and that your life is not worth something. Every life is worth so much. You have to just get through that storm.